-

- Introduction

- Setting Up Shop: Dürer’s Early Engravings

- Art for End Times: Dürer’s Woodcut Apocalypse

- Passion Projects: Depictions of Christ

- The Shape of Things: Art and Knowledge

- Career Zenith: The Master Engravings

- The Lives of Dürer’s Saints

- Dürer’s Legacy

- Checklist of Dürer works in IU Collections

Albrecht Dürer: Apocalypse and Other Masterworks from Indiana University Collections

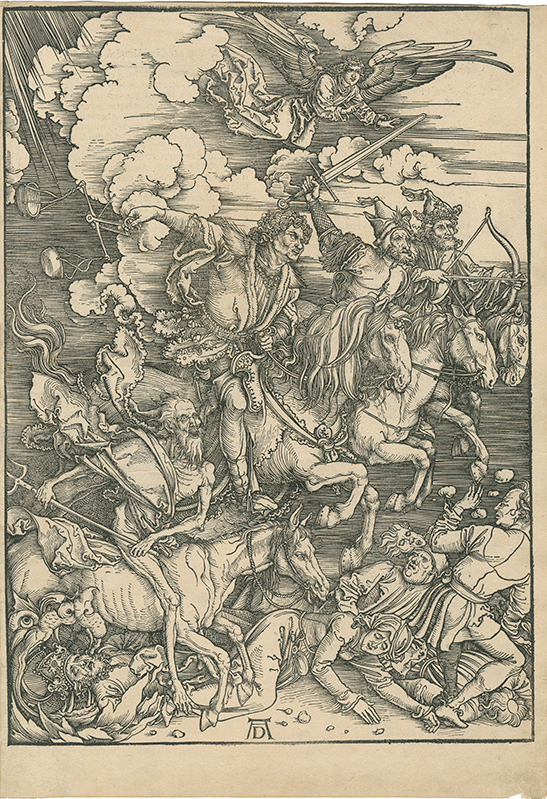

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Plate 4 from Apocalipsis cum figuris (Apocalypse), ca. 1497/98, published 1498 (Collection of George A. Poole, Jr., Lilly Library)

The name Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) is almost synonymous with the achievements of the German Renaissance, an era of extraordinary artistic and intellectual activity during which the Nuremberg artist pioneered the art of printmaking. Over three decades, Dürer would publish almost seven hundred engravings, etchings, and woodcuts that included both prints for individual sale as well as copious illustrations designed for early printed books by himself and others. Indeed, it was a book—Apocalypse—that first catapulted Dürer into the international spotlight when he published it in both German and Latin editions in 1498. These fifteen large and startling woodcuts depicted the end of the world prophesied in the biblical Revelation of Saint John with unprecedented sophistication, announcing Dürer’s remarkable talents as a printmaker to audiences throughout Europe. He would go on to become the first artist more famous, even in his own lifetime, for his prints than his paintings, emulated by younger artists, and courted by Europe’s political and intellectual elite. Not long after Dürer’s death, Erasmus of Rotterdam would specifically praise the artist’s gifts as a printmaker, eulogizing him in a now-famous turn of phrase as the “Apelles of black lines.”1

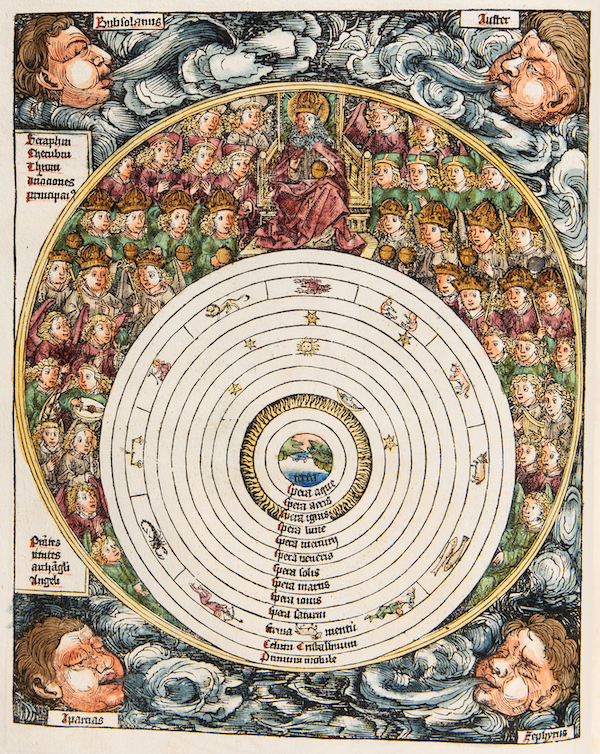

The apocalyptic horsemen, marmoreal nudes, and brooding scholars in Dürer’s prints still exert their charismatic pull today, inviting us to marvel at his prodigious ability to conjure such technically accomplished and powerfully sensuous works of art. The exhibition that accompanies this publication extends the same invitation, drawing on the rich holdings of both the Eskenazi Museum of Art and the Lilly Library to showcase more than fifty works by Dürer from Indiana University (IU) collections.2 The selection spans the length of Dürer’s career, from numerous superb impressions of early works from the 1490s to his scholarly treatise Instruction in Measurement, published in 1525. The Lilly Library’s complete Latin edition of Dürer’s woodcut Apocalypse (fig. 1)—a book rarely found in American collections—is among the exhibition’s most noteworthy highlights. Recently disbound as part of a conservation campaign, each of its newly restored woodcuts is on individual display for the first time, permitting close side-by-side comparisons of Dürer’s dramatic visual narrative.3

The presence of Dürer’s work in IU collections preceded the establishment of both the Eskenazi Museum and the Lilly Library by several decades. Alfred Mansfield Brooks, the first art instructor in the university’s Department of Freehand and Mechanical Drawing, was also first to acquire several prints by Dürer not long after he was hired in 1896. A recent Harvard University graduate, Brooks recognized the importance of giving students the opportunity to study actual works of art by acclaimed masters.4 Old Master prints were an attractive prospect because of their obvious artistic merits but also because they were still well within financial reach, unlike oil paintings by the same artists. Brooks purchased twelve woodcuts from Dürer’s Life of the Virgin as well as the artist’s etching Landscape with Cannon (fig. 36) for the early Fine Arts Collection.5 In 1963, his acquisitions were among the first prints by Dürer to officially enter the museum’s collection when it accessioned the Virgin woodcuts, although the etching was not added until 1980. The museum acquired many of Dürer’s most coveted prints (particularly his engravings) in the 1970s, under Director Thomas T. Solley with the expert guidance of IU art history professor and print collector Diether Thimme.6 The first of these core acquisitions was an impression of Adam and Eve purchased in 1971, the same year in which retrospectives of Dürer’s work were held around the world in honor of his five-hundredth birthday. A rash of pivotal acquisitions soon followed, most notably the three so-called Master Engravings (Meisterstiche), which are often regarded as Dürer’s greatest accomplishments in print. In the quest to acquire the finest available impressions, the museum has courted some of the country’s most distinguished dealers, and in at least one case replaced a lesser impression for one of better quality.7 Prints by Dürer continued to enter the museum’s collection under the leadership of subsequent directors Adelheid M. Gealt and David Brenneman. These recent additions include The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand (fig. 2)—now the oldest woodcut by the artist in its holdings—and a beautiful early impression of The Flagellation (fig. 17).

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand, ca. 1496. Woodcut on paper. Image/sheet: 15 5/16 x 11 1/8 in. (38.9 x 28.3 cm). Museum purchase with funds from Ann Edens Sanderson and Ray Morse Sanderson, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 2007.13

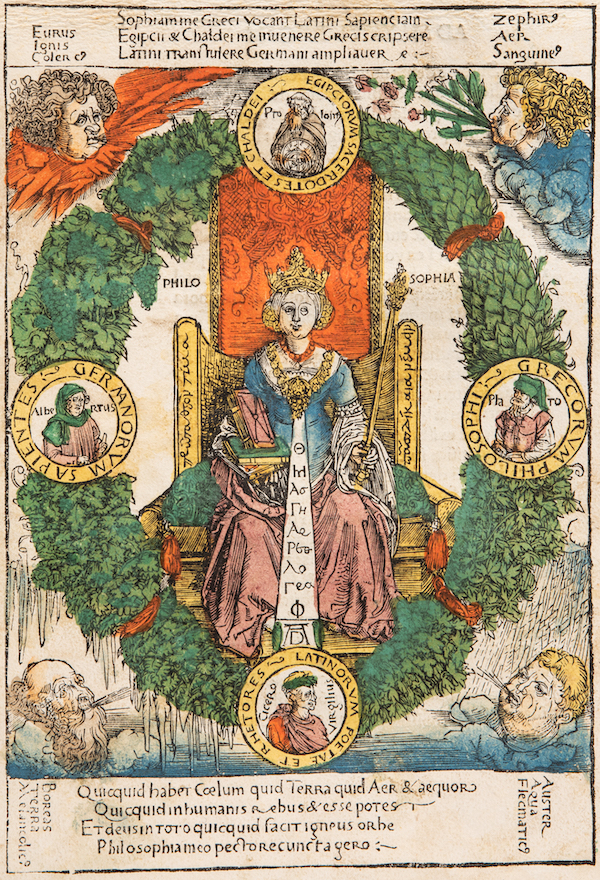

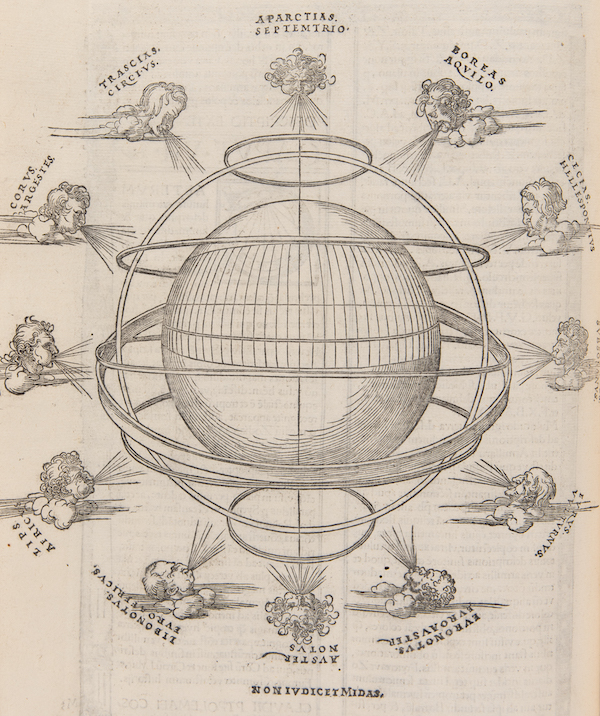

Established in 1960, the Lilly Library maintains an equally impressive body of works by Dürer that represents the legacy of such distinguished donors and benefactors as George Amos Poole, Jr. (1907–1990). Poole, a Yale University graduate and Chicago-based printer, formed a large collection of important manuscripts and early printed books that included the library’s copy of Apocalypse, one of the very few complete Latin editions from 1498 documented in American collections. Among other books from Poole’s collection on display in the accompanying exhibition are a first-edition copy of Dürer’s Instruction in Measurement as well as the Latin edition of Nuremberg Chronicle—the most ambitious illustrated book published before 1500, and one to which Dürer may also have made some youthful contributions. Poole’s collection was acquired for the library by David A. Randall after he assumed his position as its first librarian in July 1956. Since then, the Lilly has gone on to acquire still other books and collector’s albums that feature prints by Dürer, including some for books by other authors now rarely exhibited beyond the confines of specialized libraries. These include two woodcuts Dürer made for Four Books on Love by Conrad Celtis (fig. 3), an effusive tribute to early German achievements in the arts and sciences, as well as a third woodcut depicting an armillary sphere from a sixteenth-century edition of Ptolemy’s Geography (fig 4). The Lilly has also acquired a fascinating example of a modern collector’s album that contains Dürer’s woodcuts for his Small Passion, now thought to have once belonged to nineteenth-century French print scholar Pierre Alexander Robert-Dumesnil.8 Together, the library’s unusual holdings thus substantially enrich our understanding of the artist’s varied activities, both as an established artist and scholar, and conceivably also as a young and still-unknown apprentice.

Figs. 3–4

Left: Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Philosophia, from Quatuor libri amorum secundum quatuor latera Germanie (Four Books on Love), 1502 (Lilly Library); Right: Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). An Armillary Sphere, from Geographica (Geography), 1525 (Collection of Bernardo Mendel, Lilly Library)

Setting Up Shop: Dürer’s Early Engravings

Dürer opened his Nuremberg workshop in 1495 and wasted no time building a sizable print stock, amassing an inventory of some sixty engravings and woodcuts within five years. Such quick and prolific output was motivated in part by a desire to acquire the financial independence that could often elude artists relying solely on commissions for paintings and altarpieces. Yet the sheer range and complexity of these early works is also testimony to Dürer’s concerted effort to ultimately refine and expand both the formal graphic vocabulary and iconographic possibilities of traditional print media: woodcut, engraving, and etching.

Martin Schongauer (Alsatian, ca. 1430-February 2, 1491). Christ Crowned with Thorns, ca. 1480. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 6 5/16 x 4 1/2 (16 x 11.4 cm). William H. Conroy Memorial, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 71.59

Dürer’s most accomplished predecessor, the recently deceased Martin Schongauer, had already made substantial advances in the medium of engraving, enhancing it with a painter’s sense for detail and illusionism that appealed to even the most sophisticated audiences (fig. 5). Schongauer was without question the painter-printmaker on whom Dürer largely modeled himself and whom he now sought to best, but the Alsatian was not the only printmaker whose oeuvre had made a lasting impression on him. Dürer also admired the work of early Italian printmakers such as Andrea Mantegna and Antonio del Pollaiuolo, whose mythological imagery and unflinching portrayal of nude bodies provided more novel sources of inspiration. Of course, countless other visual and literary sources—from the humblest woodcut illustrations by anonymous craftsmen to the rarefied verse of Florentine poets—also found their way into Dürer’s prints. Yet if so many of these early works offered a visually stunning treatment of familiar subject matter, they could also stray into more enigmatic territory that defied easy interpretation, but which proved just as attractive to the cosmopolitan clientele Dürer so eagerly sought.

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). The Prodigal Son, ca. 1496. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 9 3/4 × 7 1/2 in. (24.8 × 19.1 cm). Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 75.60.5

The three earliest engravings by Dürer in the museum’s collection demonstrate how accomplished and diversified his work became. The Prodigal Son (fig. 6), one of the artist’s first large-scale engravings, reimagines a familiar parable first told in the Gospel According to Luke. This tale of a remorseful young man, left penniless after squandering his inheritance on wine and women, enjoyed immense popularity in the late fifteenth century and became a staple of sermons and didactic literature.9 Departing from the conventional iconography of existing woodcut illustrations, Dürer conjured a theatrical spectacle of remorse and repentance that announced both his growing mastery of the burin (the sharp steel tool used by engravers) and his ability to create original compositions whose often-contemporary settings heighten their sense of immediacy and uncanniness. Dürer’s Prodigal Son does not stand over his shepherd’s rod tending to his pigs but instead kneels right alongside them at their trough, a posture that better emphasizes the depth of his contrition. Alas, even they seem to chide him. Dürer also chose a ramshackle German barnyard pressed up against the outer walls of a small town as his setting, a novel choice of milieu that enhances the psychological tension at play. Crumbling mortar, deteriorating roof work, and an imposing dung heap all reinforce the Prodigal Son’s state of spiritual and material ruin. The artist also established an active dialogue between fore- and background for the first time by setting the Prodigal Son’s sights on the church steeple beckoning from the other side of the wall, just beyond the barnyard’s muddy confines—a poignant allusion to his desperate wish to bridge the distance and return home forgiven of his sins.

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). The Sea Monster, ca. 1498. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 9 13/16 × 7 5/8 in. (24.9 × 19.4 cm). William H. Conroy Memorial, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 72.86.1

Another early engraving by Dürer featured a subject unlike anything previously conceived by northern printmakers. The Sea Monster (fig. 7) draws on the classical tradition of the reclining female nude, a motif whose sensuousness—even in its most coldly marmoreal iterations—was as provocative as was it was unusual. The stony indifference and sleek composure of Dürer’s young maiden suggests he drew inspiration from classical statuary rather than fashioning her appearance from live models, as he may already have been doing for other prints.10 The subject clearly alludes to a long tradition of European myth and folklore concerning the abduction of beautiful women coveted by gods but also so-called “wild-men,” be they hirsute riders on horseback or seaborne hybrids like the wizened merman seen in this engraving. An early sheet of sketches now in the Albertina Museum, Vienna reveals that Dürer was exploring abduction motifs in the 1490s, including that of the beautiful Europa famously abducted by the Greek god Zeus in his guise as a bull; if there was a specific literary or visual source of inspiration for The Sea Monster, however, it remains unknown.11 Instead, it appears to be among the finest early examples of Dürer’s syncretistic powers of imagination, merging disparate imagery from both north and south to devise a compelling and original Renaissance puzzle piece that met with broad appeal.

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Saint Eustace, ca. 1501. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 14 x 10 3/16 in. (35.6 x 25.9 cm). William H. Conroy Memorial, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 73.26

In Saint Eustace (fig. 8), Dürer returned to popular devotional imagery, but his abilities and confidence as an engraver had experienced a remarkable efflorescence, visibly improved since the publication of The Prodigal Son only a few years previous. Engraved on the heels of his international breakthrough with Apocalypse, Saint Eustace is also his largest engraving and rivals the size of a small easel painting. Eustace, the patron saint of hunting, was not among the repertoire of saints engraved by Dürer’s predecessor Schongauer, but a small woodcut illustration from a German adaptation of The Golden Legend (Legenda aurea), a thirteenth-century compendium of saint’s lives, seems to have provided initial inspiration. The result is a lush, painterly engraving of magisterial scale that not only showcases Dürer’s eye for naturalistic detail but also his masterful evocation of myriad textures. Amid a clearing on the edge of the forest, the Roman soldier Eustace kneels before the stag he has been pursuing, the moment of his conversion to Christianity at hand. The miraculous vision of the Crucifix that manifests between the stag’s antlers, and from which Christ now addresses Eustace, nonetheless becomes but another detail amid the much-larger miracle of the Creation. This cosmic perspective is underscored by an abundance of creaturely life, from the group of five hunting dogs in the immediate foreground to the saint’s majestic steed, and reaching even into the farthest recesses of the background, where a starling-shaped flock of birds assumes the same uncanny sense of ornament they so often do in real life. The museum’s collection includes two copies of this remarkable print. Together, they demonstrate how the quality of impressions gradually starts to fade as the copperplate wears down. In the best early impressions, the ink has such a crisp and lustrous quality that it seems almost to float on the surface of the paper.

Art for End Times: Dürer’s Woodcut Apocalypse

Even before Dürer took up the burin, it is important to keep in mind that the art of engraving had already developed a nuanced graphic vocabulary that was very difficult to reproduce in the medium of woodcut. Even the largest and most sophisticated woodcuts still exhibited a greater simplicity of design, a constraint arising from the resistance and fragility of the pear and lime wood blocks from which they were cut, and which made them prone to breakage. Most painter-engravers, including Schongauer, thus left the humbler art of the woodcut to the anonymous artists and craftsmen who more typically produced the book illustrations and single-leaf woodcuts comprising the bulk of the print market in the late fifteenth century.

That Dürer seemed so effortlessly to transpose the more refined grammar of engraving into the woodcut medium for the first time in his Apocalypse (1498) was in part what made it so astonishing. Yet his efforts to leverage the woodcut’s dormant potential only came on the heels of another publication that surely inspired him: the Nuremberg Chronicle (Liber chronicarum). Authored by Hartmann Schedel, this lavish history of the world featured approximately 1800 illustrations made from 645 individual designs. Painters Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydendurff were contracted to produce the designs in their workshop, where Dürer had also apprenticed in the 1480s.

Wolgemut, himself one of Nuremberg’s most highly acclaimed painters, saw in the Nuremberg Chronicle an opportunity to design woodcuts which would be distinguished by an unprecedented degree of pictorial sophistication compared to those typically found in early printed books. Among the most striking designs for the Chronicle attributed to Wolgemut is one depicting the arrival of the Antichrist, made for use in the book’s own abridged account of Apocalypse, the cataclysmic chain of events prophesied to unfold ahead of Christ’s return to Earth (fig. 9). The design was an amalgamation of imagery drawn from two popular engravings by none other than Schongauer: one depicting Saint Michael locked in aerial combat with a dragon, the other a vision of Saint Anthony encircled by a mob of bullying demons (fig. 10).

Figs. 9–10

Left: Attributed to Michael Wolgemut. Arrival of the Antichrist, Folio 262v from Liber chronicarum (Nuremberg Chronicle), 1493 (Collection of George A. Poole, Jr., Lilly Library); Right: Martin Schongauer (Alsatian, ca. 1430-February 2, 1491). Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons, ca. 1470–75. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 12 1/4 x 9 1/8 in. (31.1 x 23.3 cm). William H. Conroy Memorial, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 73.29

The fact that one of the largest illustrations in the Chronicle was reserved for an apocalyptic subject was a telling sign of the contemporary zeitgeist. In the final decades of the fifteenth century, Europe seemed in the eyes of many to be hurtling toward end times. Suspicions that the half-millennium would unleash the Apocalypse were reinforced by the persistent troubles—disease, war, and famine—that befell so much of the continent in those tumultuous years. The sheer strangeness of this dreaded event understandably posed a challenge to woodcut illustrators, whose schematic designs could only really hint at its magnitude and complexity. Wolgemut’s more elaborately excecuted design substantially raised the bar.

One can easily imagine this illustration catching a young Dürer’s eye and leaving him with a lasting impression of its subject matter, as well as its formal achievements as a woodcut. The fact that he also apprenticed under Wolgemut in the late 1480s has prompted many scholars to ponder whether he may also have witnessed or even played some small role in the production of the Chronicle by creating a few designs of his own. The handful of designs attributed to him over the years include the four wind gods from The Seventh Day of Creation, which also bear some resemblance to the four winds seen in the upper register of Plate 6 from his later Apocalypse (figs. 11 and 12). As enticing as such theories can be, there is ultimately no satisfactory proof that Dürer ever had such a role, however modest, in the book’s production, or that production had in fact begun during his apprenticeship with Wolgemut.12

Figs. 11–12

Left: Sometimes attributed to Albrecht Dürer. The four winds (detail) from The Seventh Day of Creation, Folio 5v from Liber chronicarum (Nuremberg Chronicle), 1493 (Collection of George A. Poole, Jr., Lilly Library); Right: Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Four Angels Staying the Winds, Plate 6 from Apocalipsis cum figuris (Apocalypse), 1497, published 1498 (Collection of George A. Poole, Jr., Lilly Library)

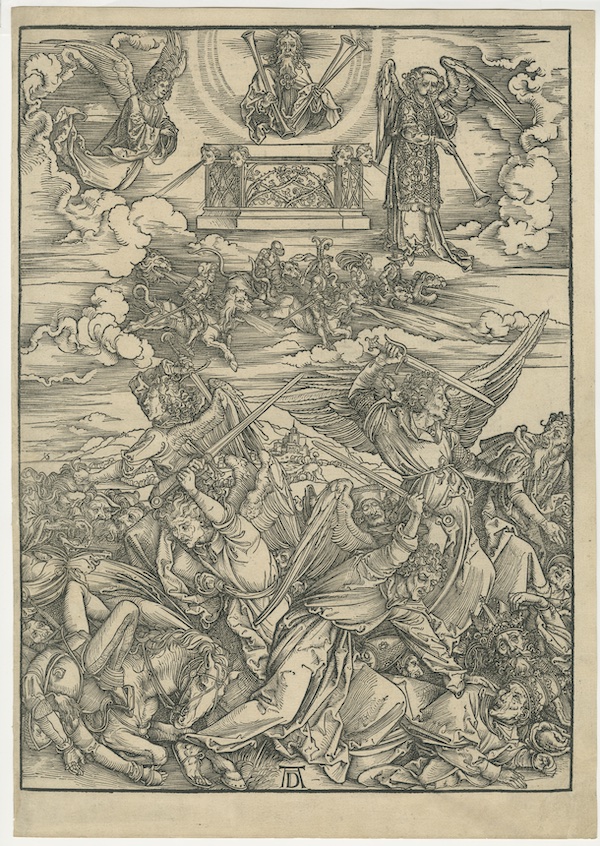

Surmising the promise of a sensational subject that would only become more topical as the half-millennium drew closer, Dürer started producing woodcuts for Apocalypse in 1496. As innovative as his compositions would prove to be, they were by no means the fruits of pure invention but designed while closely consulting existing visual resources. The most important of these was a series of woodcut illustrations that had been printed in multiple editions of the German Bible since 1478 (fig. 13).13 Dürer was especially interested in the way these woodcuts condensed their complex subject matter into such limited space. To succeed in the much larger and more ambitious format he had planned would necessitate strategic choices—artfully splicing events from different chapters together while omitting others altogether. Dürer envisioned a sequence that would remain sufficiently faithful to the biblical text while achieving a carefully choreographed sense of rhythm, an arrangement that could quickly fall apart in less capable hands. The final sequence of fifteen woodcuts are thus characterized by deliberate crests and lulls in the action, the first half focusing on scenes of God’s wrath against humanity (fig. 14), the second on the eventual defeat of the Antichrist (fig. 16). The turning point between these two sections is marked by a vividly original scene of John’s encounter with the so-called Strong Angel (fig. 15), whose appearance defies explanation as it shifts between solid and more wraithlike form, its legs stout columns that burst into flame, and its torso dissolved amid a swirling curtain of ether as John receives the book from its hand. The juxtaposition of events as they simultaneously unfold in Heaven and on Earth is also a defining element of Dürer’s compositional strategy. Nearly every woodcut in Apocalypse is bisected into these two distinct realms of action, which gradually become ever more enmeshed as things unfold.

Unknown artist. Printed by Anton Koberger. Illustration from Apocalypse: The temple and two witnesses; the beast and the witnesses; the woman and the great red dragon, ca. 1478–79, color woodcut, sheet: 4 3/4 x 7 1/2 inches, Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift of J. Lionberger Davis 101:1951;

Although Dürer would frequently publish prints for individual sale, including those eventually destined for series, he appears to have held on to the woodcuts for Apocalypse until they could be published together as a book in 1498.14 By publishing both German and Latin editions, he endeavored to reach a broad European readership for whom Latin remained the lingua franca of an educated elite, his native language of German still largely a vernacular tongue. Each woodcut faces an opposing page of text from Revelation, arranged in two columns of letterpress, and is signed with Dürer’s now-famous “AD” monogram. Although it was not unusual for printmakers to sign engravings with their monogram, Dürer was the first to sign woodcuts, marking them as his own invention and legitimating their status as works of fine art he now elevated to the same niveau as engraving.

Figs. 14–16, left to right: Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). The Four Avenging Angels, Plate 8 from Apocalipsis cum figuris (Apocalypse), ca. 1496, published 1498 (Collection of George A. Poole, Jr., Lilly Library); Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). John Devouring the Book, Plate 9 from Apocalipsis cum figuris (Apocalypse), ca. 1498, published 1498 (Collection of George A. Poole, Jr., Lilly Library); Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Saint Michael Fighting the Dragon, Plate 11 from Apocalipsis cum figuris (Apocalypse), ca. 1498, published 1498 (Collection of George A. Poole, Jr., Lilly Library)

Passion Projects: Depictions of Christ

The woodcuts for Apocalypse were not the only ones that Dürer made during this extraordinary period of productivity in the 1490s. Among the other subjects he pursued is Christ’s Passion, the account of Jesus of Nazareth’s capture and torment before his eventual crucifixion on the cross. That Dürer turned to this popular devotional subject matter is unsurprising. In the late fifteenth century, scenes from the Passion were already ubiquitous in the work of Northern European artists, including Schongauer, whose 115 engravings included a twelve-print Passion cycle and five Crucifixion scenes in addition to his magisterial Bearing of the Cross.15 For Dürer, representing the Passion was nothing less than one of art’s core purposes. As he once wrote, to do so was not just the best way to honor God but to express gratitude for the divine gift of artistic genius.16 Tirelessly exploring this subject with lifelong dedication, Dürer demonstrated more than piety by probing how the Passion responded to variations on form and content and, in so doing, vetting the artistic possibilities latent in this quintessential serial narrative.

Figs. 17–18

Left: Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). The Flagellation, Plate 5 from Large Passion, ca. 1496–97,published 1511. Woodcut on paper. Image: 15 × 10 3/4 in. (38.1 × 27.3 cm), sheet: 15 1/8 × 10 15/16 in. (38.4 × 27.8 cm). Gift of Joan W. & Walter E. Wolf, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 2016.52; Right: Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). The Lamentation, Plate 9 from Large Passion, ca. 1498–99, published 1511. Woodcut on paper. Image/sheet: 15 5/16 × 11 in. (38.9 × 27.9 cm). Woodcut on paper. Gift of Ernst Anspach, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 63.159

Much like his woodcuts for Apocalypse, the seven large Passion woodcuts Dürer completed between 1496 and 1500 were often elaborate theatrical stage sets, characterized by a pathos and pageantry that has been compared to that of the medieval Passion plays so popular in the late Middle Ages. The two early Passion woodcuts in the museum’s collection demonstrate Dürer’s pronounced attention to the punishing transformations wrought on Christ’s body by the deadly strain of his ordeal. Whereas the young, muscular Christ in The Flagellation (fig. 17) still exhibits formidable physical strength, his limp and emaciated corpse in The Lamentation (fig. 18) is an unvarnished vision of a prolonged, painful death. Dürer makes no attempt to soften the spectacle of the dead Christ by casting a faint glimmer of tranquility over his features as Schongauer often did. These and other woodcuts from the series were sold separately as Dürer completed them, but in 1511 he had them bound as his Large Passion, one of the three so-called “Large Books” he published that year, including Life of the Virgin and a second Latin edition of Apocalypse.

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Christ Enters Jerusalem, Plate 6 from Passio Christi (Small Passion), ca. 1508–1509, published 1511 (Lilly Library, donated in memory of Dr. & Mrs. Philip C. Holland; Dr. & Mrs. George Frank Holland; Dr. & Mrs. Philip T. Holland, and Mr. and Mrs. Martin M. Hugg)

Large Passion would be one of two woodcut Passion cycles Dürer released in book form whose varied handling and treatment of the subject matter evince some striking differences. The thirty-six woodcuts for Small Passion were much smaller as the title indicates—less than one-fourth the size of those in Large Passion. Dürer’s designs for it were consequently much simpler as well, but in other ways they proved uniquely effective. Unlike the crowded scenes found in Large Passion, these woodcuts maintain a stronger visual focus on the figure of Christ as he moves toward his human fate, propelling salvation history toward its foregone conclusion in the process. The traditional series of events associated with the Passion have also been extended into a cycle much broader in scope, compressing the entire biblical history of humanity into a dynamic, suspenseful narrative that acquires startling inertia. The cycle opens with Old Testament scenes from the Garden of Eden, moving up to and through the events of the Passion proper, and concluding with additional scenes that follow Christ’s Resurrection and culminate in the Last Judgment. Jordan Kantor first observed that Dürer makes subtle but undeniably strategic use of line throughout this cycle to reinforce its dynamic narrative and relentless pace, as events build quickly toward their denouement. Christ Enters Jerusalem (fig. 19), for example, depicts Christ as he is about to pass left to right through the city gates, one finger pointed ahead, while the simple horizontal hatching used to model the city walls seems almost to egg him forward.17

Figs. 20–21

Left: Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Expulsion from the Garden, Plate 3 from Passio Christi (Small Passion), 1510, published 1511 (Lilly Library, donated in memory of Dr. & Mrs. Philip C. Holland; Dr. & Mrs. George Frank Holland; Dr. & Mrs. Philip T. Holland, and Mr. and Mrs. Martin M. Hugg); Right: Johann Mommard (Flemish, active 1590–1627), after Dürer. Expulsion from the Garden, 1587. Woodcut on paper. Image/sheet: 6 3/4 × 5 1/8 in. (17.1 × 13 cm). Gift of Mrs. Julia King and Mr. Jasper King, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 82.39.3

Bound copies of Small Passion proved both affordable and exceedingly popular, and the woodcuts for it were also quick to draw the attention of copyists and imitators. Copies that were nearly indistinguishable from Dürer’s own hand were also produced in the late sixteenth century during the years of the so-called Dürer Renaissance, when posthumous interest in his prints crested anew. Two such copies by Flemish printmaker Johann Mommard in the museum’s collection reveal just how exacting these imitations could be, right down to the artist’s signature monogram. Only after prolonged scrutiny might one notice, for example, that the line of Adam’s buttocks is slightly longer in Mommard’s copy of Expulsion from the Garden (compare figs. 20 and 21); the two woodcuts are otherwise virtually indistinguishable. A modern album containing most of Dürer’s original Small Passion woodcuts in the Lilly’s collection also demonstrates how later collectors pasted these prints into albums one by one as they were acquired, at times out of sequence and obscuring the text on the verso of sheets once sold as part of the bound set.18

Figs.22–23

Left: Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Christ on the Mount of Olives, Plate 2 from Engraved Passion, 1508, published 1513. Image: 4 9/16 x 2 13/16 in. (11.6 x 7.2 cm), sheet: 5 1/16 x 3 5/16 in. (12.9 x 8.4 cm). Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John H. Myers, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 83.24B; Right: Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Christ Carrying the Cross, Plate 10 from Engraved Passion, 1512, published 1513. Image: 4 9/16 x 2 15/16 in. (11.6 x 7.5 cm), sheet: 5 1/8 x 3 7/16 in. (13 x 8.7 cm). Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John H. Myers, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 83.24J

Dürer’s woodcut Passion cycles were not his only treatment of this theme in print. Between 1507 and 1512, he also completed a cycle of exquisite small engravings that he published as a complete set in 1513.19 Quieter and more introspective than the woodcut cycles, the prints in the Engraved Passion exude a distinct aesthetic appeal of their own: On one hand is their exceptional delicacy of line, which cannot be replicated in woodcut on such a small scale. On the other is Dürer’s new and expressive use of chiaroscuro, which imbues them with a brooding ambience and emphasizes their strongly emotional tenor. Some of the most atmospheric prints in this cycle are true nocturnes such as the opening scene, Christ on the Mount of Olives (fig. 22). Here, Christ throws up his hands in a moment of unrestrained despair, spot-lit not by the luminous glow of the moon but by a radiant angel, while his companions sleep under cover of darkness. Gone is the speed and urgency that propelled Small Passion forward. In its place is a quiet but palpable psychological tension that instead encourages viewers to dwell on each print at length and absorb myriad details as they emerge from the shadows. Dürer was evidently proud of his work on this cycle, which he gave away on his 1521 trip to the Netherlands to numerous benefactors and other persons of distinction including Margaret of Austria (then Governess of the Habsburg Netherlands), who financed his trip. As his bookkeeping indicates, a complete set of these engravings was also expensive; at twice the cost of his woodcut Passions, it could be purchased for the price of an ivory comb.20

The Shape of Things: Art and Knowledge

Although traditional Christian imagery clearly had pride of place in Dürer’s printed oeuvre, the pursuit of knowledge that characterized the sixteenth-century Humanist tradition was also something he took seriously. His wish to elevate the role of the artist in the German-speaking territories—to assume rank among scholars rather than “mere” craftsmen—motivated his choice of projects from the very beginning of his printmaking career. In Dürer’s view, the learned artist was obligated to master abstract principles of geometry while also learning to draw from nature, and thereby assert one’s intellectual merits alongside one’s peers in the traditional liberal arts. Toward the end of his lifetime, Dürer would eventually publish a series of three treatises on various practical and theoretical applications of geometry as well. His theoretical positions would change over the years, particularly regarding questions of human proportion, but his desire to wed the notions of craft and intellect under the rubric of “art” (Kunst)—a word Dürer himself helped to popularize—was a constant stimulus.21

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Nemesis (The Great Fortune), ca. 1501. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 13 × 9 1/16 in. (33 × 23 cm). Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 75.60.6

Still early in his career, Dürer found himself motivated but also rankled by the achievements of his Italian contemporaries, whose work he then felt revealed the secrets of perfect human form, a perfection he felt still eluded him despite so many other personal accomplishments. In a letter written to his close friend Willibald Pirckheimer, Dürer recalls how he once asked the Italian artist Jacopo de Barbari to share the secrets of proportion with him after seeing several of Barbari’s human figures; perhaps fearful of helping such a talented rival, Barbari refused.22 It was, says Dürer, an incident that only hardened his resolve to beat the Italians at their own game and fathom proportion for himself. Over the next two years, he pursued the subject tirelessly: immersing himself in studies of the Vitruvian canon, making carefully constructed technical drawings with his compass, and exploring myriad subtleties of gesture and pose.

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Adam and Eve, 1504. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 9 3/4 x 7 9/16 in. (24.8 x 19.2 cm). William H. Conroy Memorial, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 71.27

His efforts bore fruit in 1504, when he published his engraving Adam and Eve (fig. 25), his most highly praised achievement since the appearance of Apocalypse six years prior. The idealized bodies of the biblical first couple are modeled with lines of such exceptional subtlety that they seem almost to dissolve, their bodies gleaming white like marble in brilliant contrast to the dark forested wood behind them. Dürer had chosen prototypes from classical mythology for his perfected human specimens: Adam was modeled on the Apollo Belvedere, a marble Roman copy of an ancient Greek statue that had recently been excavated and put on display in the Vatican gardens. Although Dürer never saw the Apollo Belvedere firsthand, likenesses of this celebrated statue, with its famous contrapposto (counterpoise), circulated throughout Europe in prints and drawings he knew well. For Eve, Dürer consulted depictions of the “modest Venus” (Venus pudica), based on an original fourth-century sculpture by Praxiteles and so-called for the way Venus holds her hand to discreetly conceal her sex.

If these idealized figures were meant to be the stars of the show, everything else about the engraving was just as fastidiously calculated to declare Dürer’s erudition. Nothing about it is modest—not even the artist’s signature, inscribed on a conspicuous cartouche hanging from a branch of ash and announcing in Latin that “Albrecht Dürer of the North made this in 1504.” The flora and fauna featured in the engraving evoke naturalistic forms and textures, adapted in many cases from the artist’s numerous life studies. They also reveal the artist’s calculated usage of natural symbolism, as in his choice of animals closely associated with contemporary theories of the four humors. Humoral theory posited that a balance between four bodily substances—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—determined four basic human temperaments. In Christian adaptations of this ancient tradition, the four humors were said to have been perfectly balanced until the Fall, an idea Dürer plays upon here by including creatures specifically meant to represent this state of balance in its final moments: sanguine hare, choleric cat, melancholic stag, and phlegmatic ox.

If Apocalypse secured Dürer’s fame, Adam and Eve established his mastery of the supposed secrets of the human form, which had until then been the exclusive provenance of Italian artists working within established canons. With time, Dürer grew increasingly skeptical of geometry’s potential to fully parse and explain nature’s unruly multitude of bodily forms. Yet geometry remained the artist’s bread and butter, and the treatises he published in the 1520s represented a scholarly achievement that was another first for a German artist. Unlike Italy, the German-speaking territories had no existing theoretical tradition of writing about art. Dürer himself established this tradition, circumstances that pressed him on no small number of occasions to invent new words for concepts that did not yet exist in the German language.

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). The Small Horse, 1505. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 6 7/16 × 4 3/16 in. (16.4 × 10.6 cm). William H. Conroy Memorial, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 72.127.2

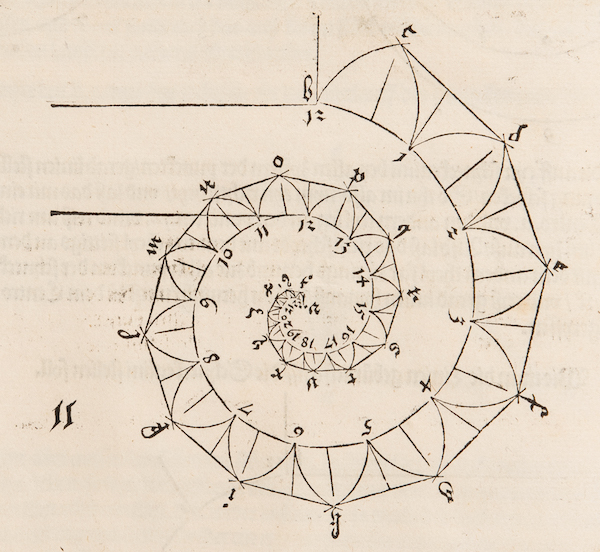

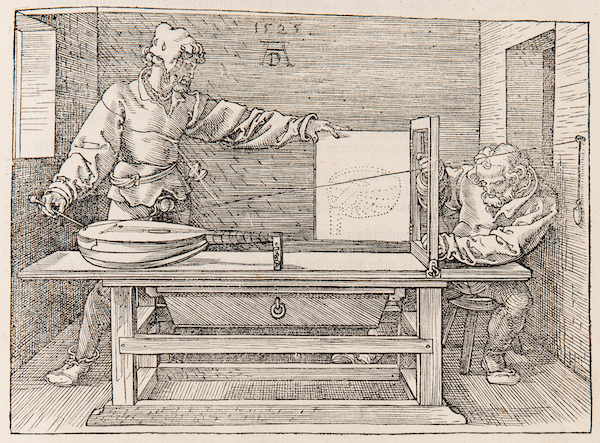

All three treatises appeared in rapid succession toward the end of Dürer’s life starting with Instruction in Measurement (1525/1538), which was followed by Treatise on Fortification (1527) and Treatise on Human Proportion (1528). A fourth treatise on the proportions of a horse—an animal that fascinated Dürer—never appeared, since the drafts were thought stolen and purportedly plagiarized, possibly by one of Dürer’s most prolific artistic contemporaries, printmaker Sebald Beham. Evidence for Dürer’s ongoing studies of equine proportion in the early 1500s can nonetheless be found in his engraving The Small Horse (fig. 26), in which the artist explored the use of geometric principles to construct its warm-blooded stallion.

The best-known of these publications is Instruction in Measurement, two first-edition copies of which are in the Lilly’s collections. Conceived primarily as a practical introduction to geometry for artists, the book treats a broad spectrum of topics richly illustrated with proofs and diagrams (fig. 27), from linear geometry and typography to perspective and architecture. Throughout, Dürer’s tone moves between dryly academic discussions and witty, even polemical subject matter with equal facility, as in one section where he illustrates a series of monuments modeled on triumphal columns but dedicated to thoroughly unorthodox themes, such as a memorial to the recent Peasant’s War and another dedicated to a “drunkard.” Illustrations like these tip into moral satire even as they elucidate geometrical problems. The final section of the treatise is also noteworthy for its informative illustrations of gridded screens and other devices used by artists to achieve single-point perspective. Some of these contraptions appear to be quite complex, such as the one featured in an illustration of a man drawing a lute (fig. 28). Through careful orchestration of thread and frame, the artist ensures he will construct the lute so that it is properly foreshortened.23

Figs. 27–28

Left: Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Example of a spiral form, Folio A5r from Unterweisung der Messung (Instruction in Measurement), 1525 (Collection of George A. Poole, Jr., Lilly Library); Right: Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Man drawing a lute, Folio Q3r from Unterweisung der Messung (Instruction in Measurement), 1525 (Collection of George A. Poole, Jr., Lilly Library)

Career Zenith: The Master Engravings

The conspicuous presence of a sandglass in each of Dürer’s three famous Master Engravings (Meisterstiche) suggests some sort of shared relationship between them—a prescient awareness of time as a limited resource and of the transience of earthly life. The rider in Knight, Death, and the Devil (fig. 29) passes a skeletal figure brandishing the first of these hourglasses in the manner of a direct threat. A conspicuously large hourglass attached to the rear wall in Jerome in His Study (fig. 30) hovers just above the saint’s head as he leans over his podium. And in Melencolia I (fig. 31), yet another ornate hourglass is hung amid the clutter of objects, a constant reminder of time spent contemplating the mysteries of the mute polyhedron that haunt the titular figure.

For a long time, details like this tempted Dürer’s interpreters to posit that the Master Engravings were deliberately designed as a triptych or even part of a tetraptych (four-part grouping)—a sustained meditation on everything from virtuous Christian living to the four humors.24 Attempts to divine from them some unambiguous message, however, have nonetheless faltered for the most part on irresolvable uncertainties and inconsistencies as puzzling as Melencolia’s polyhedron. Indeed, whether Dürer ever envisioned the Master Engravings as a triptych is something lost to posterity, since what little evidence there is suggests that, if anything, only Jerome and Melencolia I were possibly designed as pendants.25 All such claims must in any case remain speculative, and in fact the term “Master Engravings” is itself a conceit that was invented in the nineteenth century.

That the Master Engravings are still traditionally hung alongside one another in museums and print galleries is testimony to their virtuosity if not their perceived affinities. Indeed, the Master Engravings rightfully belong together as Dürer’s three most formidable accomplishments in the medium of engraving, made in the 1510s at the zenith of his career. On their own, too, each of these engravings still poses interpretive conundrums, although in the history of their reception since the early twentieth century a select number of readings have emerged that continue to maintain the upper hand.

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Knight, Death, and the Devil, 1513. Engraving on paper. Image: 9 3/8 x 7 5/16 in. (23.8 x 18.6 cm), sheet: 10 x 7 1/2 in. (25.4 x 19.1 cm). Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 76.107

The eerie Knight, Death, and the Devil presents horse and rider accompanied by a hound as they negotiate a rocky cliff-side path set in a desolate and foreboding stretch of landscape. Aside from a single lizard just underfoot, their environs seem all but denuded of life, a barrenness fit for the menacing roadside specters that trail the knight in his wake. Dürer referred to this engraving only as his “rider” (Reuter), remaining mum on the question of his identity and prompting all manner of speculation from various partisans by the time of the first Dürer Renaissance around 1600. Today, the popular conventional title Knight, Death, and the Devil harkens back to one such early interpretation favored by Nuremberg collectors. According to this local legend, a watchman by the name of Philipp Rink encountered both Death and the Devil one night when lost in the woods. It is certainly possible Dürer had this legend in mind to judge by the two ghastly figures he conceived. Death is the emaciated skeletal figure holding out the hourglass, while the Devil is a goatish hybrid with one too many horns and outsized wattles that make his appearance as grotesque as it is almost comical. Whether Dürer’s rider has indeed encountered figures that materialize along his path, or whether they possibly represent mere figments of his imagination, is another question. Regardless, the rider’s stoic advance forward suggests a grit and determination in the face of demonic adversaries, prompting many interpreters to read him instead as an embodiment of the resilient Christian soldier, the miles christianus celebrated in a famous verse by Dürer’s contemporary Erasmus of Rotterdam. Still others have suggested the rider is perhaps less wholesome than he may at first seem, his antiquated armor and his lance, accessorized with a bushy foxtail, evoking the medieval robber bandits of yore, who once patrolled back roads looking for unsuspecting travelers.

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Jerome in His Study, 1514. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 9 9/16 × 7 5/16 in. (24.3 × 18.6 cm). Museum purchase in Honor of Diether Thimme, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 78.13

Unlike Dürer’s rider, the identity of the saint in the artist’s next Master Engraving is beyond doubt. Saint Jerome is easy to recognize even without reference to the engraving’s title, ensconced in his studiolo amid familiar attributes, from the broad-rim hat that hangs just behind him to his companionable lion dozing in the foreground. The cult of Jerome remained alive and well among humanist intellectuals in Northern Europe, who idolized the church father’s scholarly achievements as an exegete and translator of the Latin Vulgate, and saw their most venerated contemporary, Erasmus of Rotterdam, as Jerome’s rightful successor. The saint assumed a prominent role in Dürer’s printed oeuvre as well, where he is depicted on six separate occasions, including one print made using the still more experimental medium of drypoint.26 In Jerome in His Study, the saint assumes his most familiar guise as scholar-saint immersed in his work, the glowing nimbus of light about his head a telltale sign of an industrious divine intellect.

Formally, too, Dürer’s engraving is quite different than Knight, Death, and the Devil. Jerome’s chamber is an explicit lesson in construction according to the principles of central perspective. The engraving’s elaborate architectonic arrangement of beams, walls, and platforms guides us toward the farthest recesses of the room while at the same time keeping us curiously at bay, as if waiting to be summoned. The ambience is defined not by stark linear contrasts, as in Knight, Death, and the Devil, but by a soft silvery glow. Its warmth is enhanced by the striking pattern of dappled sunlight reflected along a wall of large recessed windows—a wonderfully evocative and much-celebrated detail that exploits the white of the sheet to great effect. Dürer’s engraving may, of course, be a straightforward tribute to the vita contemplativa that the departs somewhat from the moodier aura of his other two Master Engravings. On closer scrutiny, however, an uncanny air of threat also seems to fill the room, as Matthias Mende has ventured to suggest. In addition to the various memento mori scattered about—skull, crucifix, hourglass, even the dried gourd—Mende reconsiders the very room itself. The sunlight is pleasant enough, even beautiful, but the room has an airless quality reinforced by the lack of any obvious exit and windows that do not appear to open. Even the back wall has the appearance of a later addition made to keep the ceiling from collapsing—a detail suggested by its abrupt alignment with the rear window, which has resulted in a conspicuous crack.27 One is tempted to consider whether not only Jerome’s mortality but also his legacy are depicted as if under imminent threat, subject to both the ravages of time and religious ebb tides.

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Melencolia I, 1514. Engraving on paper. Image: 9 3/8 x 7 3/8 in. (23.8 x 18.7 cm), plate: 9 1/2 x 7 1/2 in. (24.1 x 19.1 cm), sheet: 9 15/16 x 7 7/8 in. (25.2 x 20 cm). William H. Conroy Memorial, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 73.37

Melencolia I, the last of Dürer’s three Master Engravings, is not only his most famous print but also the one on which scholars have most often tested their interpretive mettle. The darkened features and brooding comportment of the woman in this image assert her apparent identity as a female personification of melancholia: the temperament most closely associated in medieval culture with both depressive stupor and splenetic rage. According to artistic convention, the melancholic was typically portrayed head in hand or in a slumberous state. Dürer’s melancholic also rests head in hand, while the putto and dog that accompany her doze in restive slumber, accentuating the engraving’s pervasive mood of apathy. The source of Melencolia’s gloom appears to be the massive polyhedron propped up on a ledge as if for study, leaving her baffled and exhausted in her attempts to comprehend it. The putto has stopped scribbling in his tablet, while Melencolia frowns over the caliper she holds in her lap and stares into the distance, an arsenal of tools strewn willy-nilly at her feet. Dürer’s contemporaries would have recognized signs of her attempts to counteract her saturnine state, including the leafy crown of herbs thought to quell melancholia’s effects or the so-called “magic square” of numbers on the wall behind her, associated with the sanguine Jupiter.28

The tools of geometry were also the tools of the artist, but they were not attributes traditionally linked with melancholia. By the sixteenth century, however, the latter was increasingly regarded as an affliction that was also closely associated with creative genius—an idea that also seems to have interested Dürer and would have no doubt flattered him.29 Indeed, the cultural history of this development has since become one of the master keys thought to unlock the engraving’s secrets. Among the first to champion this view, Erwin Panofsky famously described Melencolia I as a spiritual self-portrait of the artist, a claim that has since become central to how this engraving is typically understood. At the same time, the dazzling and often contradictory wealth of objects and props that surround Melencolia, to say nothing of the curious twilit milieu she occupies, still prompt endless debates waged through the lens of myriad disciplines and agendas, from mathematics and astronomy to popular conspiracy theory. One is tempted to ask if Dürer’s engraving, like the ladder in its background, leads us nowhere in particular. Instead, the artist sends us on a wayward but pleasurable search for meaning. Mitchell Merback recently suggested that this may be precisely the point, as if to enact a kind of homeopathic remedy for the melancholic’s occasionally self-destructive pursuit of genius, a pursuit Dürer identified as the necessary sufferings of the artist—in one moment divine, in the next saturnine.30

The Lives of Dürer’s Saints

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Jerome in His Cell, 1511. Woodcut on paper. Image: 9 1/4 x 6 3/16 in. (23.5 x 15.7 cm), sheet: 9 7/16 x 6 7/16 in. (24 x 16.4 cm). William H. Conroy Memorial, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 73.25.2

In 1511, a couple years before Dürer engraved his atmospheric Jerome in His Study, he made Jerome in His Cell (fig. 32), a lesser-known woodcut of the saint that likewise featured him in his studio immersed in his work. It is the same basic subject matter, yet the woodcut Jerome seems considerably more mundane than miraculous, more earthly than ethereal, quiet rather than disquieting. Leaning over a small podium, the saint cuts a large commanding figure, his head crowned not by a nimbus of radiant light but only a growing bald spot surrounded by wispy curls of hair. His studiolo is solid and well-appointed, a niche built into the corner of a larger room partially obscured behind the curtain. Absent are the uncanny specters of the large gourd and skull that occupy his chambers in the later engraving, as are any signs of architectural wear. The pathos that so often characterizes Dürer’s representations of saints is not in evidence.

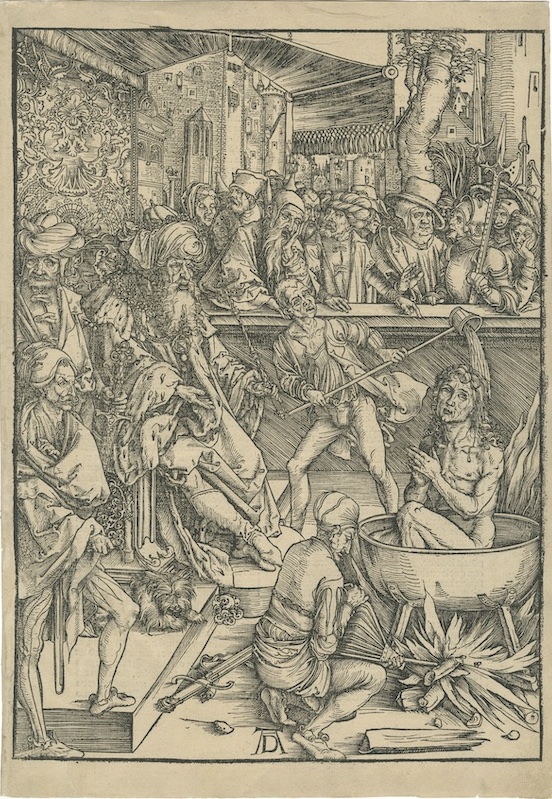

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Martyrdom of Saint John, Plate 1 from Apocalipsis cum figuris (Apocalypse), ca. 1496-97, published 1498 (Collection of George A. Poole, Jr., Lilly Library)

More than forty individual saints appear throughout Dürer’s printed oeuvre, some of them, like Jerome, on multiple occasions. In earlier years, Dürer’s saints were frequently the subject of theatrical scenes depicting preternatural incidents and visceral punishments, as in the woodcut Martyrdom of Saint John that prefaces Apocalypse, where John prays while being doused with ladles of boiling oil (fig. 33). This late medieval taste for such dramatic and even graphic anecdotes concerning the saints had literary roots in The Golden Legend (Legenda aurea), a thirteenth-century compendium of saints’ lives that was by 1500 the most popular book in print other than the Bible. Dürer himself was no doubt familiar with German-language legendaries based on Voragine’s work, such as the Passional (Der Heiligen Leben), first published in 1471/72 and re-issued by Koberger in 1488. With time, Dürer’s portrayals of saints came to favor quieter and more contemplative scenes, often shedding even the most residual signs of their otherworldly stature. This was by no means a programmatic shift, but certainly one that better accommodated religious fault lines that seemed by the 1510s to be in a perpetual state of flux and augured the expansion of the Lutheran Reformation to new German-speaking territories, including Nuremberg. By the 1520s, the apocryphal legends of saints that had once been so universally popular were increasingly viewed by many in Germany as unreliable fictions, distractions from the truth of God’s word.31

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Saint Paul, 1514. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 4 11/16 × 3 in. (11.9 × 7.6 cm). Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 77.21.2

As one of the twelve Apostles, the closest disciples of Jesus, Saint Paul was rapidly becoming one of the most influential ecclesiastical figures for the nascent Reformation faith. Indeed, Dürer’s initial decision to engrave him in 1514 seems to have been motivated in part by recent conversations among Reform-minded colleagues in Nuremberg in which he, too, had participated. The statuesque simplicity of Dürer’s Saint Paul (fig. 34) is inspired by traditional late medieval representations of the Apostles, yet it also belies the significant effort he put into determining its final composition.32 Paul appears with his familiar attributes of book and sword standing atop a small hillock in front of a low brick structure. Clutching the open book to his breast, he conspicuously points to one passage with his right index finger as if to emphasize the power of the word while casting an inward glance in the opposite direction. Demand for apostolic imagery in these years crested, and although Dürer was planning to publish an engraved cycle of the Twelve Apostles, he would never finish it. Paul was to be the first of five apparent engravings for this cycle that were released at intermittent junctures between 1514 and 1526. Although this project never came to completion, Dürer successfully redirected his own growing interest in the Apostles into his life-sized painted diptych, the austere but monumental Four Apostles (1526; Alte Pinakothek, Munich), which he conceived for and gifted to the Nuremberg City Hall.

Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Saint Anthony Reading, 1519. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 3 7/8 x 5 9/16 in. (9.8 x 14.1 cm). William H. Conroy Memorial, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 72.127.3

Dürer’s late engraving Saint Anthony Reading (fig. 35) returns to a legendary apocryphal figure. Saint Anthony was not only venerated in the Middle Ages for his miraculous ability to heal painful diseases of the skin such as shingles, often called Saint Anthony’s Fire, but also for the episode of his temptation by demons—the same diabolic incident that Schongauer had depicted in his influential engraving from the 1470s. In keeping with the more subdued and contemplative ambiance of his late engravings, Dürer’s Anthony seems almost to follow Paul’s lead, completely absorbed by the small book he reads. Behind him rise the towers and spires of one of Dürer’s most beautifully engraved cityscapes, mirrored by his tall double-cross staff, which the saint has planted upright beside him. It is as if the saint’s magical healing powers yield here to the curative power of God’s word alone. The oblong format of this engraving is exceedingly unusual among Dürer’s prints, utilized only here and in one other instance to emphasize the attractions of landscape (fig. 36). The small size of Dürer’s engraving has been the subject of some speculation as well, prompting the suggestion that it may even have been intended as a New Year’s card. That Anthony could have turned up on such a card would certainly have been fitting: among the wishes traditionally exchanged around the New Year were those for a long life, like Anthony—himself a rumored centenarian.33

By 1522, the year that Andreas Karlstadt called for a war on religious art throughout Germany. Dürer had almost entirely ceased to depict saints—at this point, a calculated decision. Only the Apostles continued to make appearances in his art, since they appear alongside Jesus in the Gospels. Like Luther, Dürer disapproved of the destructive tactics favored by radically minded iconoclasts in those years. At the same time, however, his art also evolved in ways that very much registered the tidal shifts taking place in contemporary religious discourse. In 1525, three years before Dürer died, the Nuremberg City Council made the city’s adoption of the Lutheran faith official.

Dürer’s Legacy

After the rich and prolific experimentation of the 1510s, Dürer’s print output slowed during the last decade of his life. Most of his remaining woodcuts and engravings were devoted to portraiture and select religious themes that reflected a late and more austere style. When Dürer embarked on a trip to the Netherlands in 1521, hoping to secure the pension funds that had been guaranteed to him by the recently deceased Maximilian, he brought with him a generous stock of his earlier prints to gift and to sell. He remained proud of his earlier work, which remained popular, and gave away numerous impressions to contacts and benefactors during what proved to be his final journey abroad. He would return to Nuremberg a year later, having contracted the infection that would slowly sap his health until he eventually died in 1528.

By then one of Europe’s most famous and esteemed artists, his death met with a flood of eulogies published by scholars and enthusiasts, including Erasmus of Rotterdam and Joachim Camerarius. His estate remained for several years in the custody of his wife Agnes and brother Endres before his blocks and remaining inventory were dispersed among early collectors, many of whom were members of royalty like Emperor Rudolf II. What remained of the sixteenth century gradually saw the rise of the first Dürer Renaissance toward its end, a period in which artists frequently imitated and emulated his printed oeuvre for reasons as noble as they could occasionally be nefarious—as in the case of Mommard’s extraordinary copies of Small Passion, an apparent attempt to pirate Dürer’s work. Other printmakers were more respectful, making copies they signed with their own monograms and paying tribute to the artist even as they now sought to meet and, in some instances, surpass his achievements.

Figs. 36–37

Left: Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). Landscape with Cannon, 1518. Etching (iron) on paper. Image: 8 9/16 × 12 11/16 in. (21.7 × 32.2 cm), sheet: 8 5/8 × 12 9/16 in. (21.9 × 31.9 cm). Former Fine Arts Collection, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 80.70.1; Right: Hieronymus Hopfer (German, active 1520–30), after Dürer. The Cannon, 1530. Etching (copper) on paper. Image: 7 9/16 × 11 in. (19.2 × 27.9 cm), sheet: 8 1/4 x 11 3/4 in. (21 x 29.8 cm). Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 76.144.2

Hieronymus Hopfer, for example, demonstrated his skills with the etching needle by imitating Dürer’s last etching, Landscape with Cannon (figs. 36 and 37). Etching on copper rather than iron plates, Hopfer achieved a crispness of line that gives his etching a sparkling, lucid quality and readily distinguishes it from Dürer’s original. And in 1594, Hendrick Goltzius—then Europe’s most famous living printmaker—completed his virtuoso series Life of the Virgin, a cycle of six designs composed in the manner of other artists. The fourth plate, The Circumcision (fig. 38), emulated Dürer’s high style with such uncanny exactitude that many initially believed it to show a newfound composition by the artist himself (compare figs. 38 and 39).

Figs. 38–39

Left: Albrecht Dürer (German, May 21, 1471-April 6, 1528). The Circumcision, Plate 11 from Life of the Virgin, ca. 1504. Image: 11 11/16 x 8 5/16 in. (29.7 x 21.1 cm),sheet: 13 1/8 x 9 3/8 in. (33.3 x 23.8 cm). Former Fine Arts Collection, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 63.197; Right: Hendrick Goltzius (Dutch, 1558–1617), in the manner of Dürer. The Circumcision, Plate 4 from Life of the Virgin, 1594, published 1593–94. Engraving on paper. Image: 18 1/4 × 13 13/16 in. (46.4 × 35.1 cm), plate: 18 3/4 × 13 15/16 in. (47.6 × 35.4 cm), sheet: 20 3/4 × 15 5/8 in. (52.7 × 39.7 cm). Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 72.131.4

Interest in Dürer has waxed and waned in the centuries since, peaking at somewhat predictable intervals clustered around the anniversaries of his birth and death; yet his canonical status has never been questioned. As his oeuvre was gradually catalogued and became more widely known during the nineteenth century, his posthumous reputation grew. The grand European and American museums that first opened their doors in the late 1800s paid tribute to the artist’s enduring legacy not just with acquisitions but also carved likenesses that look down at visitors from halls and entryways. As of this writing, the five-hundredth anniversary of the artist’s death is fast approaching in 2028, promising renewed scrutiny of his undeniable achievements as well as new insights into this most fascinating and gifted artist-scholar.

Leah Marie Chizek

Fess Graduate Assistant in the Department of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs at the Eskenazi Museum of Art

Albrecht Dürer: Apocalypse and Other Masterworks from Indiana University Collections was on view in the Rhonda and Anthony Moravec Gallery at the Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art July 1–December 19, 2021.

Notes

1 The revised and expanded version of Joseph Meder’s influential catalogue raisonné remains the most comprehensive authority on Dürer’s printed oeuvre and lists 158 woodcuts, 95 engravings, 6 etchings, and 1 drypoint firmly attributed to the artist. This tally excludes the many woodcut illustrations he made for theoretical treatises as well as books by other authors, which substantially increases this number. See Rainer Schoch, Matthias Mende, and Anna Scherbaum, eds., Dürer: Das druckgraphische Werk, 3 vols. (Munich: Prestel, 2001–04).

2 Albrecht Dürer: Apocalypse and Other Masterworks from Indiana University Collections, The Rhonda and Anthony Moravec Gallery, Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, July 1–December 19, 2021.

3 The Incunabula Short-Title Catalogue lists one other copy of the first Latin edition held by Harvard’s Houghton Library: https://data.cerl.org/istc/ij00226000. The ISTC is not an exhaustive listing, however, and does not exclude the possibility of additional copies in American collections, including one copy held in the Rosenbach Collection (Philadelphia).

4 Nanette Esseck Brewer, “Alfred Mansfield Brooks: The Man Who Brought Art to IU,” 200: The Bicentennial Magazine 2, no. 1 (January 2019): 18–20.

5 The Eskenazi Museum of Art’s impression of Dürer’s etching appears to be the same previously unknown third state that was recently described for the first time by German collector Maik Bindewald in 2016. To date, only a limited number of these third-state impressions have been documented in American museum collections, including the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. See Maik Bindewald, “An Undiscovered State of Albrecht Dürer’s Large Cannon,” Art in Print 5, no. 5 (January–February 2016): 6-7.

6 Following his passing, the museum purchased the print Saint Jerome in His Study in Professor Thimme’s honor, “in light of his contribution to the Museum’s Dürer collection.” Museum Policy Committee Minutes, July 13, 1978 (Eskenazi Museum files).

7 In 1975, the Eskenazi Museum of Art sold the impression of Adam and Eve it acquired in 1971 and purchased another impression of finer quality from dealer David Tunick, a well-known specialist in Old Master prints.

8 The Lilly album contains all but the title page and colophon from Dürer’s Small Passion. The woodcuts are not bound in the conventional order. Each is mounted on a blank page other than for pencil annotations that indicate their English titles. After inspecting the album for the museum’s exhibition, I now believe the signature on the flyleaf, until now not fully transcribed, belongs to Alexandre Pierre François Robert-Dumesnil (1778–1864), a notable collector and historian of French prints. In 1835, Robert-Dumesnil published an ambitious catalogue raisonné on the French peintre-graveurs meant to supplement the work of Austrian scholar Adam von Bartsch (1757–1821), the most prolific cataloguer of European prints prior to his death.

9 For details concerning these illustrations, see Schoch, Mende, and Scherbaum, vol. 1, cat. no. 9. Dürer almost certainly knew at least some of these illustrations.

10 The use of live female models to study the human form was a practice virtually unheard of in German territories at such an early date, where the artistic culture remained more conservative than in Italy. On Dürer’s early use of models, see among others JoAnne G. Bernstein, “The Female Model and the Renaissance Nude: Dürer, Giorgione, and Raphael,” Artibus et Historiae 13 (1992): 49–63.

11 For a fuller discussion of possible sources, see Schoch, Mende, and Scherbaum, vol. 1, cat. no. 21.

12 Opinions concerning which of these woodcuts Dürer may have designed vary. For further details see especially Schoch, Mende, and Scherbaum (2004), vol. 3: 477–79. Today, evidence increasingly seems to suggest that Dürer’s period as an apprentice was over before production on the illustrations for the Chronicle was properly underway.

13 All nine of these anonymous woodcuts were first published in the Cologne Bible of 1478. They were later acquired by Anton Koberger, who reused eight of them for a new edition of the German Bible he published in 1483. Dürer appeared to be familiar with all nine of these illustrations, suggesting he consulted a copy of the Cologne Bible rather than Koberger’s while working on this project. Schoch, Mende, and Scherbaum, vol. 2: 63–64.

14 Today, Dürer is still credited as the first Western artist to publish his own book. Nonetheless, all indications are that his godfather, Anton Koberger, supplied substantial technical assistance. Koberger printed the Latin edition on Dürer’s behalf, and possibly also the German.

15 The checklist first compiled in 1925 by Max Lehrs remains the most comprehensive record of Schongauer’s engravings. See Max Lehrs, Martin Schongauer: The Complete Engravings, revised and annotated by Alan Shestack and Charles Minott (San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 2005).

16 “I shall not labor in vain if I set down at which may be useful for painting. For the art of painting is employed in the service of the church and by it the sufferings of Christ are set forth.” The Literary Remains of Albrecht Dürer, translated by William Martin Conway (Cambridge: 1889), 196.

17 Jordan Kantor, Dürer’s Passions (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 2000): 30–31.

18 Bound versions of both woodcut Passion cycles included Latin verse by Abbott Bernhard Chelidonius on the verso and printed in letterpress.

19 It is not entirely clear whether Dürer designed the engraving Saint Peter and Saint John at the Gate of the Temple as part of this cycle. Dürer often used a single folio-sized sheet to print up to four small engravings, which could mean he printed it together with three other engravings destined for the Passion cycle solely to leverage his existing paper stock. The subject is certainly not one that is usually associated with the Passion. See among many others, Jeffrey Chipps Smith, Dürer (London: Phaidon, 2012), 220.

20 For further details of the cycle’s production and reception, see especially Mende, Schoch, and Scherbaum, vol. 1, 125–29; here on 128.

21 In German, the word Kunst weds the notions of ability and knowledge—craft and intellect—through the verbs können (to have an ability/be able) and kennen (to know). See Chipps Smith (2012), 125 and Erwin Panofsky, The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1943), 242. In the latter volume, see also Panofsky’s interesting chapter on Dürer as a theorist of art, 242–84.

22 The circumstances of any such meeting between Dürer and Barbari are uncertain. Barbari spent most of his career in Northern Europe, suggesting Dürer may have met the artist at some point while the latter was passing through Nuremberg. It is also plausible that the two met when Dürer traveled for the first time to Italy in 1494, although this would have taken place nearly a decade before the eventual publication of Adam and Eve.

23 Dürer’s most famous illustration from Instruction in Measurement (Schoch, Mende, and Scherbaum, vol. 3, cat. no. 274.216) was not added until the posthumous edition of 1538, supplied to the publisher together with several more by Dürer’s wife Agnes. It depicts a bearded Renaissance artist observing a nude female model through a gridded screen—once again, a perfect illustration of actual methods that were used to achieve one-point central perspective during the Renaissance. Of course, it also perfectly encapsulates the gendered politics of the Renaissance gaze, with its many conceits of mastery.

24 In his 1974 dissertation, art historian Peter-Klaus Schuster suggested that the Master Engravings in fact constitute a foursome, and hence a portrait of the four human temperaments, together with Adam and Eve. Although his theory has found little endorsement, Schuster’s elaborate argument remains testimony to the cryptic attractions the Master Engravings present to scholars.

25 Bookkeeping records from Dürer’s 1521 trip to the Netherlands make note of several occasions on which Saint Jerome and Melencolia I were dispersed together without the earlier Knight, Death, and the Devil. This has sometimes been taken to mean that the two 1514 engravings were conceived as pendants although there is no concrete evidence for this; indeed, there are numerous reasons why his various clients may have acquired this specific pair at the same time.

26 Today, a woodcut illustration depicting Jerome as he translates the Bible is generally considered the first print firmly attributable to Dürer (Schoch et al., vol. 3, cat. no. 261.1). The illustration appears to be a Latin edition of Jerome’s letters published in 1492 by Nicolaus Kessler of Basel. This puts it among woodcut illustrations attributed to Dürer as he was still in his journeyman years.

27 See Mende’s extended entry on this engraving in Schoch, Mende, and Scherbaum, vol. 1, cat. no. 70. I am inclined to agree with his observation that the engraving’s cozier qualities have caused its uncannier aspects to go frequently overlooked.

28 The rows and columns in Dürer’s magic square—a concept we associate today with Sudoku and other numerical puzzles—always yield the sum “34.” In astrology, this number was itself associated with the planet Jupiter, which was in turn associated with sanguine qualities. Hence, it represents an astrological talisman of sorts meant to counter Saturn’s melancholic (saturnine) qualities.

29 There is a massive literature on the topic of Dürer’s purported artistic and intellectual interest in the melancholia. Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl’s work on this topic has had a profound and lasting impact on the engraving’s interpretation, at times to the detriment of fostering counter perspectives. See Panofsky and Saxl, Dürer’s Melencolia I: Eine quellen- und typengeschichtliche Untersuchung (Leipzig/Berlin, 1923), as well as their English collaboration with Raymond Klibansky, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art (New York: Basic Books, 1964). For an especially astute critique of their arguments, see Keith Moxey, “Panofsky’s Melancholia” in The Practice of Theory: Poststructuralism, Cultural Politics, and Art History. Edited by Moxey (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994): 65–78.

30 Mitchell B. Merback, Perfection’s Therapy: An Essay on Albrecht Dürer’s Melencolia I (London: Zone, 2018).

31 The 1510s ushered in a period of religious introspection and reform even before Martin Luther famously nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the doors of Wittenberg Cathedral in 1517. Dürer had great sympathy for the Lutheran cause. Although he never met Luther himself, he embraced the young monk’s views together with his most eminent peers and colleagues in Nuremberg. Many, if not most of them, were from the early 1510s on members of the so-called Sodalitas Staupiziana, an informal group of reform-minded civic leaders that was named in honor of Luther’s progressive mentor Johann von Staupitz, himself a frequent visitor to Nuremberg.

32 For further elaboration, see Schoch, Mende, and Scherbaum, vol. 1, cat. no. 74.

33 Mende cited by Anna Scherbaum in Schoch, Mende, and Scherbaum (2001), vol. 1, cat. no. 87.

Works by Albrecht Dürer in Indiana University Collections

All works marked with an asterisk are on display in the exhibition.

Prints by Dürer in the Eskenazi Museum of Art Collection

- The Prodigal Son, ca. 1496. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 9 3/4 × 7 1/2 in. (24.8 × 19.1 cm). 75.60.5*

- Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand, ca. 1496. Woodcut on paper. Image/sheet: 15 5/16 x 11 1/8 in. (38.9 x 28.3 cm). Museum purchase with funds from Ann Edens Sanderson and Ray Morse Sanderson, 2007.13*

- The Sea Monster, ca. 1498. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 9 13/16 × 7 5/8 in. (24.9 × 19.4 cm). William H. Conroy Memorial, 72.86.1*

- The Beast with Two Horns Like a Lamb, Plate 12 from Apocalypse, ca. 1496/97, published 1498. Woodcut on paper. Image: 15 7/16 × 11 in. (39.2 × 27.9 cm), sheet: 15 9/16 x 11 1/8 in. (39.5 x 28.3 cm). Morton and Marie Bradley Memorial Collection, 98.25

- The Flagellation, Plate 5 from Large Passion, ca. 1496–97, published 1511. Woodcut on paper. Image: 15 × 10 3/4 in. (38.1 × 27.3 cm), sheet: 15 1/8 × 10 15/16 in. (38.4 × 27.8 cm). Gift of Joan W. & Walter E. Wolf, 2016.52*

- The Lamentation, Plate 9 from Large Passion, ca. 1498–99, published 1511. Woodcut on paper. Image/sheet: 15 5/16 × 11 in. (38.9 × 27.9 cm). Woodcut on paper. Gift of Ernst Anspach, 63.159*

- Saint Eustace, ca. 1501. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 14 × 10 3/16 in. (35.6 × 25.9 cm). William H. Conroy Memorial, 73.26*

- Saint Eustace, ca. 1501. Engraving on paper. Image: 14 × 10 1/8 in. (35.6 × 25.7 cm), sheet: 14 13/16 × 10 5/16 in. (37.6 × 26.2 cm). Gift of the Estate of Elisabeth Perkins Myers, 2015.23*

- Nemesis (The Great Fortune), ca. 1501. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 13 × 9 1/16 in. (33 × 23 cm). 75.60.6*

- Adam and Eve, 1504. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 9 3/4 x 7 9/16 in. (24.8 x 19.2 cm). William H. Conroy Memorial, 71.27*

- The Small Horse, 1505. Engraving on paper. Image/sheet: 6 7/16 × 4 3/16 in. (16.4 × 10.6 cm). William H. Conroy Memorial, 72.127.2*

- Selections from Life of the Virgin, published 1511. Cycle of twenty woodcuts on paper.

Individual woodblocks completed between 1502 and 1511 and sold separately before being sold as a set. Formerly part of the Fine Arts Collection.

- Plate 1: Virgin and Child on Crescent Moon, ca. 1511. Image/sheet (trimmed): 8 3/8 × 7 7/8 in. (21.3 × 20 cm). 63.199

- Plate 2: Rejection of Joachim’s Offering, ca. 1504. Image: 11 11/16 × 8 3/8 in. (29.7 × 21.3 cm), sheet: 11 7/8 × 8 1/2 in. (30.2 × 21.6 cm). 63.195

- Plate 3: Joachim and the Angel, ca. 1504. Image/sheet: 10 3/4 × 8 1/4 in. (27.3 × 21 cm). 63.192

- Plate 5: Birth of the Virgin, ca. 1503. Image: 11 5/8 × 8 1/4 in. (29.5 × 21 cm), sheet: 11 7/8 × 8 7/16 in. (30.2 × 21.4 cm). 63.191

- Plate 6: Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, ca. 1503. Image: 11 11/16 × 8 1/4 in. (29.7 × 21 cm), sheet: 12 1/16 × 8 5/8 in. (30.6 × 21.9 cm). 63.196

- Plate 7: The Betrothal of the Virgin, ca. 1504. Image/sheet: 11 1/2 × 8 3/16 in. (29.2 × 20.8 cm). 76.2.5

- Plate 9: The Visitation, 1503/1504. Image/sheet: 11 9/16 x 8 3/16 in. (29.4 x 20.8 cm), mount: 12 1/2 × 9 1/16 in. (31.8 × 23 cm). 63.198

- Plate 10: The Adoration of the Shepherds (The Nativity), 1502/1503. Image: 11 13/16 × 8 3/16 in. (30 × 20.8 cm), sheet: 11 7/8 × 8 1/4 in. (30.2 × 21 cm). 63.190

- Plate 11: The Circumcision, ca. 1504. Image: 11 11/16 x 8 5/16 in. (29.7 x 21.1 cm), sheet: 13 1/8 x 9 3/8 in. (33.3 x 23.8 cm). 63.197*

- Plate 14: The Flight into Egypt, ca. 1504. Image: 11 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. (30 × 21 cm), sheet: 11 15/16 × 8 5/16 in. (30.3 × 21.1 cm). 63.189

- Plate 15: The Rest on the Flight to Egypt, ca. 1502. Image: 11 13/16 × 8 3/8 in. (30 × 21.3 cm), sheet: 12 3/16 × 8 3/4 in. (31 × 22.2 cm). 63.200