The exhibition Looking at Form and Surface in African Ceramics, curated by Diane Pelrine, presents a selection of ceramics from the collections of the Eskenazi Museum of Art and Professor Emeritus of Fine Arts William Itter. On view in the Raymond and Laura Wielgus Gallery, it is the inaugural Focus exhibition for Arts of Africa, Oceania, and Indigenous Art of the Americas. The Focus Gallery is a small, rotating exhibition space that features a range of artworks that address current issues, showcase curatorial and IU student research, and display works in the collection not often on view. The museum’s other galleries also include spaces for Focus exhibitions.

Looking at Form and Surface in African Ceramics highlights African ceramics and invites a discussion on the significant role of women artists in Africa. It also introduces visitors to African ceramics from the twentieth century, primarily those from West and Central Africa, as well as a few ceramics from East Africa (fig. 1). The attention and recognition of women artists coincides with a separate initiative at the Eskenazi Museum of Art focused on women artists, A Space of Their Own, which is made possible through the Jane Fortune Fund for Virtual Advancement of Women Artists. This essay explores intersections between gender and design in the African ceramics on view in the exhibition, while also considering the roles of the collector and display by examining Itter’s collection and the new Focus Gallery space.

Figs. 1–3

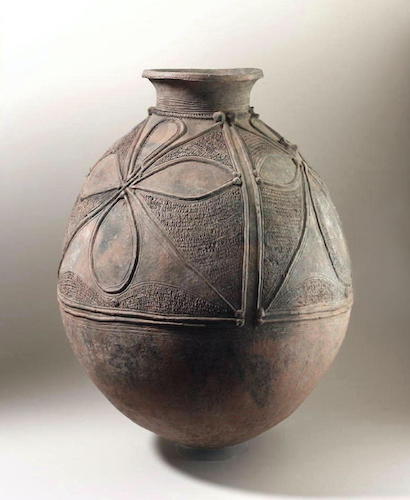

Top: Installation view of the Focus Gallery exhibition Looking at Form and Surface in African Ceramics, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University. Bottom: Artist unidentified. Ha peoples, Tanzania. Storage Vessel. 20th century. Clay, fiber, and incrustation, 17 ¼ x 18 in. Collection of William M. Itter. Photograph: William Itter; Artist unidentified. Idoma peoples, Nigeria. Water Storage Vessel. 20th century. Clay, 22 × 19 in. Gift of William M. Itter, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 2017.93. Photograph: William Itter

Twentieth-Century Ceramics in Africa

Installation view of the Focus Gallery exhibition Looking at Form and Surface in African Ceramics, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University

Women have frequently been the main producers of ceramics in many different African societies, though men also make them in some places. For ceramics and other arts like weaving and metalworking, such artistic practices are often gendered in that it is culturally acceptable for women or men to take part in such activities; women or men weave cloth depending on location, while metalwork is often practiced among men. In some African societies, cultural taboos or historical practices have guided which genders are typically included or excluded from participating. Yet contemporary artistic production across the African continent is dynamic and ever evolving with some women and men challenging long-standing gender norms attached to certain visual arts, including ceramics.

This exhibition’s focus on form and surface invites visitors to consider how the visual aspects and designs of twentieth-century African ceramics reveal artists’ creativity, skills, and expertise as well as various approaches to ceramics across the continent. Each vessel takes shape in different forms, including large-scale pots that carry great presence through their impressive size and other vessels that are smaller with a slender or wide opening—distinctions that suggest their different uses (figs. 2 and 3 illustrate the variety of ceramic forms represented in this display). The exhibition displays ceramic pots that would have been used for different purposes, including large storage vessels, cooking pots, and containers to hold water and beer (fig. 4).

Figs. 5–6

Left: Installation view of the Focus Gallery exhibition Looking at Form and Surface in African Ceramics, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University; Right: Artist unidentified. Igbo peoples, Nigeria. Vessel. 20th century. Clay, 28 ½ x 21 ½ in. Collection of William M. Itter. Photograph: William Itter

Ceramicists create surface decoration through attention to pattern, pigment, and texture, such as adding thin rows of coils in this lidded vessel that is possibly from Gurunsi culture shown on the far right of this image (fig. 5) and the surface design on this vessel from Igbo peoples (fig. 6). This storage vessel from Chewa society illustrates a distinctive technique to creating surface decoration, in which women paint abstract designs with drip marks using a liquid made from root sap (fig. 7). These different works are shown together in this exhibition because of Itter’s collecting interests in which attention to form and surface have informed his approach to collecting ceramics. Itter said, “I often wonder in great curiosity what were the things that generated the form. Of course the human condition is present in every pot, from the long run of things that are like what we refer to the pots with a lip, with a neck, shoulder, with a handle, with a waist [and with a foot].”1 Itter connects here aspects of a ceramic’s form that correlates to language referencing the body.

Artist unidentified. Chewa peoples, Malawi. Storage vessel, 20th century. Clay, 16 x 16 in. Gift of William M. Itter, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 2017.95. Photograph: William Itter

Ceramics have a long history in the African continent and are associated with ancient societies, including well-known terracotta works from Nok in West Africa (present-day Nigeria) dating to 500 BCE. Terracotta figures made during the thirteenth to eighteenth centuries in Djenné (such as this equestrian figure in the museum’s collection 76.98.1)—an important historic city (in present-day Mali) that actively shaped trade and religion in West Africa—and Bankoni (also present-day Mali) are currently on view in the Arts of Africa section of the Wielgus Gallery (see also this clay figure 82.12). Ceramics were and continue to be significant to many aspects of life in Africa, from uses within homes for cooking to spiritual settings and political contexts. Through the wide-ranging and integral presence of ceramics in daily life and special occasions, the women who make such ceramics not only influence the design of these objects but also contribute to shaping visual culture more broadly. Yet the status of ceramicists within their communities varies by place. For the ceramics displayed in this exhibition, we do not know the artists’ names—an issue addressed in this Feature essay by Emma Fulce.

African ceramics in the Eskenazi’s collection include some artworks by named artists, including the well-known Kenyan born artist Magdalene Odundo. Ceramist Clive Sithole’s work is on view in the Wielgus Gallery’s section on artist identities in Africa (fig. 8). A well-known Zulu ceramist, Sithole’s work relies upon Zulu ceramic traditions (see fig. 9), yet it is also in many ways unconventional. Sithole is a man working in what has been and predominately continues to be a women's field for Zulu peoples. As this vessel shows (fig. 8), he uses motifs that are based upon the work of ancient Greek artists and French cave paintings as much as they are upon Zulu traditions and images related to Zulu life. Yet Sithole continues to use historical Zulu ceramic forms, such as the coil-building technique and uphiso, which is traditionally used for the transport of beer and water.

Figs. 8–9

Left: Clive Sithole (South African, born 1971). Uphiso, late 20th to early 21st century. Clay, 18 x 15 5/16 in. Museum purchase with funds from the Class of 1949 Endowed Curatorship for the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 2007.15; Right: Artist unidentified. Zulu peoples, South Africa. Beer vessel (Ukhamba), 20th century. Clay, 10 ½ x 13 ½ in. Gift of William M. Itter, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 2014.87. Photograph: William Itter

Additionally, Itter has donated other African ceramics to the museum that are on view elsewhere in the Wielgus Gallery, including this water container displayed in a section on the importance of community in African art (figs. 10 and 11). African ceramics from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are included in the introduction area of the Wielgus Gallery, a space designed to offer visitors building blocks for understanding arts from Africa, Oceania, and Indigenous Art of the Americas (figs. 12–15). Featuring African ceramics in this introductory space, as well as in the Focus Gallery, allows visitors to better understand the variety of ceramics in Africa as well as the care, skill, and attention to aesthetics applied to making ceramics for utilitarian functions.

Figs. 10–11

Left: Ceramic vessel on view in the Raymond and Laura Wielgus Gallery of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and Indigenous Art of the Americas, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University; Right: Artist unidentified. Makonde peoples, Mozambique. Water Container, Chilongo Chakumuto. Clay and kaolin, 21 x 26 in. Gift of William M. Itter, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 2015.154. Photograph: William Itter

William Itter’s Collection of African Art and Contributions to the Eskenazi Museum of Art

Itter has had a long relationship with both Indiana University and the Eskenazi Museum of Art (fig. 16) starting with his first donation to the museum in 1974, and his first donation to the arts of Africa, Oceanic, and Indigenous Art of the Americas department in 2006. He has since made generous donations and loans to the museum over the years. Itter taught at IU for over three decades until retiring in 2006. He is a painter with wide-ranging interests in visual arts, and directed the fundamental studio program at IU. His late wife, Diane Itter, was also an artist who worked with fiber and both of their work is represented within the Eskenazi Museum’s collection. In discussing how they each developed their artistic interests in painting and textiles, Itter remarked on their shared interests in the pictorial element, edges, and spatial effects. Itter continued “we were always intrigued by the mystery of what the hand could do.”2

Figs. 12–15, clockwise from top left: Installation view of the introductory section of the Raymond and Laura Wielgus Gallery of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and Indigenous Art of the Americas, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University; Artist unidentified. Teke or Sengele peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Water Bottle. Clay and pigment, 13 3/4 x 7 1/2 in. Gift of William M. Itter, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University 2015.148. Photograph: William Itter; Artist unidentified. Tusyan or Karaboro peoples, Burkina Faso. Palm Wine Vessel. Clay, 21 ½ x 17 in. Gift of William M. Itter, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University 2008.228. Photograph: William Itter; Artist unidentified. Baatonu peoples, Republic of Bénin. Shea-Butter Jar. Clay, 12 ½ x 12 in. Gift of William M. Itter, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University 2014.84. Photograph: William Itter

When William and Diane Itter were collecting artworks, they looked for textiles, baskets, folk art, ceramics, and other media that they could use as a visual library for their own artistic work and teaching. Itter’s collection has expanded over the years to include more than a thousand artworks comprised of different media and artworks made in different parts of the world, such as textiles and coverlets, Native American baskets and crafts, Oceanic pottery, and arts from South America (fig. 17). Itter’s collecting interests for the arts displayed in the Wielgus Gallery started in the 1970s, and he purchased his first African ceramic vessel in 1990. Since then, Itter has continued to collect African ceramics and became interested in a number of topics related to African ceramics, including the idea of transformation in pottery connected to forms in other visual arts and the spiritual uses of some ceramics. Reflecting on what unites his wide-ranging collecting interests. Itter remarked, “I have to stretch back, pull back from the details, I have to say that the variety of the human hand at work, is part of the human condition.”3

Figs. 16–17

Left: Professor Emeritus of Fine Arts William Itter. Photo courtesy of IU Studios; Right: Artwork display in the home of William Itter. Photo courtesy of IU Studios

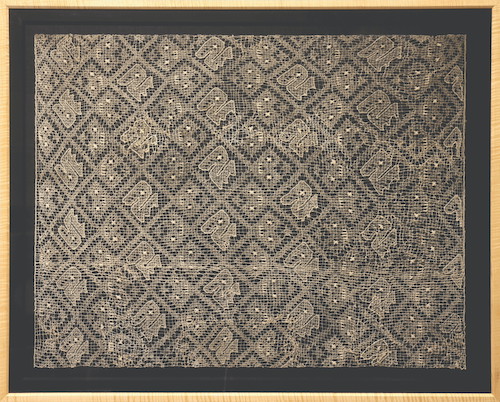

Itter’s collecting interests include textiles, and the Wielgus Gallery features African textiles and a textile from ancient Peru that Itter loaned to the museum (fig. 18). His knowledge, eye as a collector, artistic skills, and close relationship with the museum have also led to close consultation between himself and the curator in several instances, including the display of his Kuba textiles in the textile gallery as part of the museum’s reopening installation (fig. 19). In addition to mounting and framing the works for this section, Itter was instrumental in figuring out their display, providing a detailed map of the textiles’ arrangement, the spacing between them, and their organization.

Itter has been a supporter of the museum in several ways, including the naming of the museum’s new “William and Diane Itter Objects Study.” This technology-equipped space allows students and scholars to closely study 3D art objects in a way that was not previously possible. In 2018 Itter also gave the museum a transformative estate gift that includes his collection and also established the William and Diane Itter Museum of Art Conservation and Research Endowment for ensuring the care of and attention to the collection in the future. Itter’s incredible generosity with the objects he has donated, loaned, and promised to the museum will allow for the care, display, and continued study of objects within the permanent collection.

Figs. 18–19

Left: Artist unidentified. Chimú or Chancay culture, Peru. Embroidered Gauze Head Wrap, ca. 1000. Cotton, 30 ¾ x 39 ¾ in. Collection of William M. Itter. Photograph: William Itter; Right: A selection of raffia cloths from Kuba society in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the collection of William M. Itter. Installation view of the African Textiles Gallery within the Wielgus Gallery, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University

Focus Gallery Exhibitions

In addition to the new object viewing room, the renovation project also involved reconceptualizing rotating exhibition spaces in the museum’s permanent collection galleries. Before the museum's two-year renovation, the Wielgus Gallery contained what was previously called the Focalpoint Gallery, a space used for a range of small temporary exhibitions based predominantly in the permanent collection of African, Oceanic, and Indigenous Art of the Americas, but with occasional loans. Focalpoint exhibitions displayed works that were typically not on view or light sensitive, meaning that they cannot be on view long term in a gallery. These short-term exhibitions were often created in conjunction with an IU class, or as part of a Graduate Assistant’s research work—a wonderful learning opportunity for students to share rigorous scholarly research with students and the public. Focalpoint exhibition topics ranged greatly, from discussions of authenticity to repair of African objects and the careers of specific collectors. Works loaned to the museum by William Itter were also displayed in Focalpoint exhibitions, including The Patterned Kingdom: Surface Design among the Kuba (2013).

During the renovation, the Focalpoint Gallery was renamed the Focus Gallery, though it will continue much of the same purpose. Whereas the Focalpoint Gallery was located within the African art area in the previous layout, the Focus Gallery is now in a central location connected to all three world areas—Africa, Oceania, and Indigenous Americas. In the current Focus exhibition, the selection of African ceramics brings attention to artworks not often on view in the gallery while also highlighting Itter’s significant contributions, spanning more than four decades. We similarly hope that future Focus exhibitions will expand understandings of artistic practices featured in the Wielgus Gallery in ways that are timely and connected to the larger academic community at Indiana University.

Allison Martino

Laura and Raymond Wielgus Curator of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and Indigenous Art of the Americas

Emma Fulce

Collections Specialist

Looking at Form and Surface in African Ceramics was curated by Diane Pelrine, former Laura and Raymond Wielgus Curator of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and Indigenous Art of the Americas, 1986–2017.

Notes

1 William Itter, Personal communication, February 26, 2021.

2 William Itter, Personal communication, February 26, 2021.

3 William Itter, Personal communication, February 26, 2021.

Share this feature

How to cite this page

Martino, Allison and Emma Fulce. "Focus: African Ceramics and the Collection of William M. Itter." Collections Online. Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 2021. https://artmuseum.indiana.edu/collections-online/features/africa-oceania-indig-america/african-ceramics-itter.php.