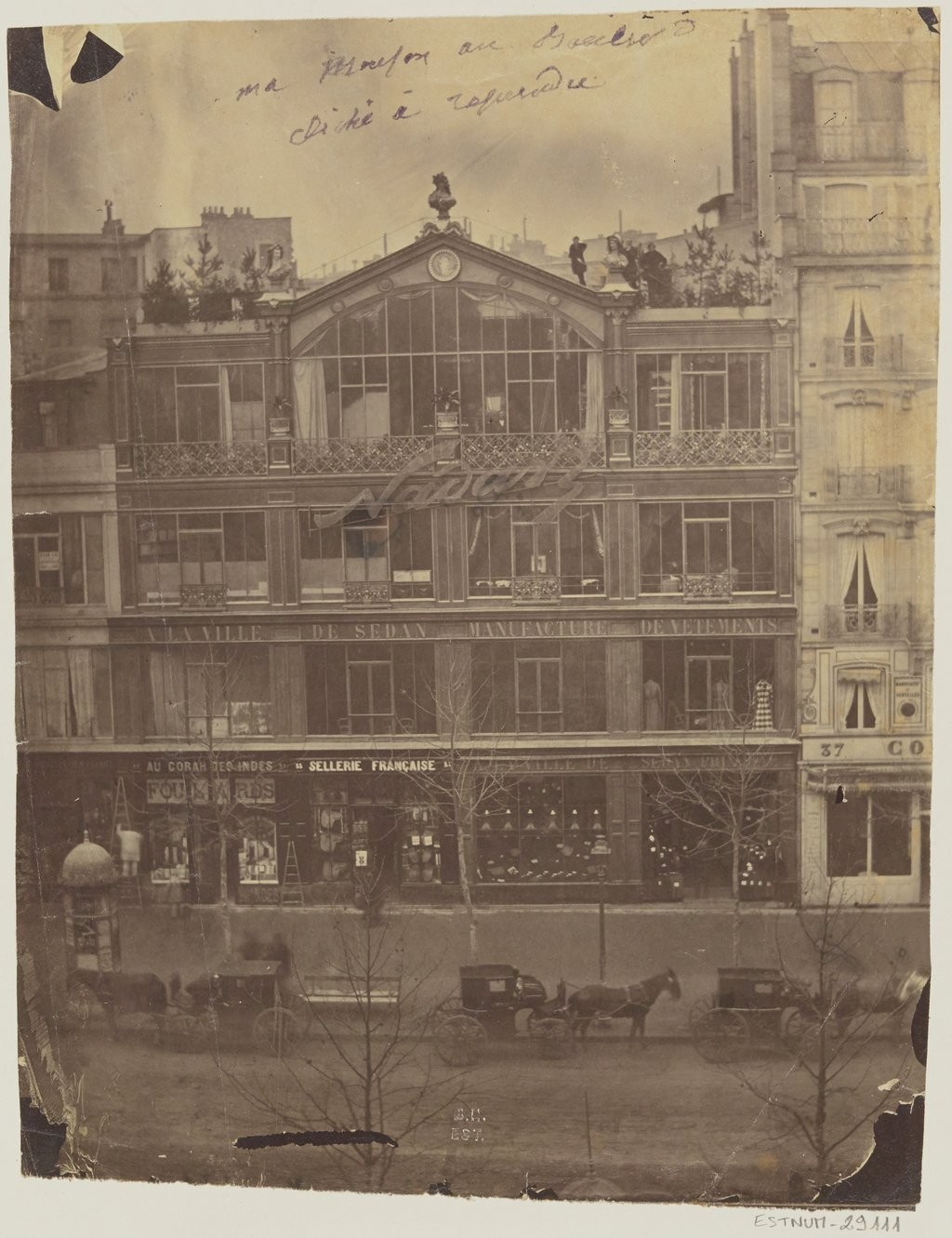

In 1874, a group of artists who called themselves the Société anonyme des peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs etc. (Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Printmakers etc.) organized an independent exhibition in Paris, launching the movement that would become known as Impressionism. The exhibition, held at the former studio of the photographer Nadar on the boulevard des Capucines, was the realization of efforts made over the better part of a decade (fig. 1).

Félix Nadar (French, 1820–1910). Façade of the studio at 35 Boulevard des Capucines, around 1861. Albumen print from a collodion glass negative, 9 1/2 x 7 1/2 in. BnF, Prints and Photographs Department, EO-15 (1)-FOL © Bibliothèque nationale de France

Frustrated with the decisions and policies of the official French arts administration in the late 1860s, a younger generation of artists took action against the status quo. At the center of their grievances was the perceived inconsistency of the annual Salon. The Salon jury accepted artists one year and rejected them the next, putting seemingly arbitrary limits on their ability to exhibit and sell their work. In 1867, these tensions came to a head when Frédéric Bazille, Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Sisley all had their works rejected from the Salon. These artists tried—but ultimately failed—to organize an independent exhibition outside of the auspices of the state-sponsored system in the late 1860s.1

It was not until 1874 that the group was able to secure the funding necessary to rent an exhibition space and to promote their venture. Between 1874 and 1886, they would organize eight group exhibitions that included paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, and other, more unusual works like the gouache and watercolor paintings on silk fans exhibited by Edgar Degas and Pissarro at the 1879 exhibition. In the beginning, some conservative critics ridiculed the artists and their exhibitions, calling out the sketchy quality of their landscape paintings in particular. However, the group had their early supporters, with Emile Cardon writing for La Presse: “There is here a new avenue open to those who believe that in order for art to advance, there needs to be a greater amount of freedom than that granted by the administration.”2

Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926). Impression, Sunrise, 1872. Oil on canvas, 18.9 in x 24.8 in. Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris © Christian Baraja - Ancienne collection Ernest Hoschedé - Ancienne collection Georges de Bellio

Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (fig. 2) was singled out for criticism by Louis Leroy in his review of the 1874 exhibition for Le Charivari, giving the group their name, “les impressionnistes,” or the Impressionists.3 At the exhibitions that followed, the composition of the group changed but their central mission remained the same: to present an independent exhibition of works that reflected their artistic concerns. While the exhibitions included artists working in diverse styles and media, they became best-known for the techniques adopted by the core members of the group, including short, unblended brushstrokes; an emphasis on spontaneity; and experiments with the effects of light. The development of synthetic pigments led to artists using more vivid colors in their paintings and Impressionist painters often chose not to varnish their canvases.

Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926). Le Bassin d’Argenteuil, 1874. Oil on canvas, 21 3/4 x 25 7/8 in. Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 76.15

The Eskenazi Museum of Art’s collection includes a number of works by Impressionist artists. Monet’s Le Bassin d’Argenteuil (fig. 3) was painted soon after the first Impressionist exhibition. Its loose, unmodulated brushstrokes are typical of Monet’s landscape paintings from this period. The expansion of railway lines in the second half of the nineteenth century made travel outside of urban areas easier and Parisians began to spend their weekends in the small towns that surrounded the city. Images of the countryside and of suburban leisure became popular subjects for Impressionist painters like Monet, who lived in Argenteuil from 1871 until 1878. Monet was particularly interested in the industrialization of the modern landscape and he took care to paint factories and smokestacks at the horizon line. In the bottom right of the canvas, Monet included his studio boat, which allowed the artist to paint views from the Seine river that were otherwise inaccessible.

Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848–1894). L’ Yerres, effet du pluie, 1875. Oil on canvas, 31 5/8 x 23 1/4 in. Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 71.40.2

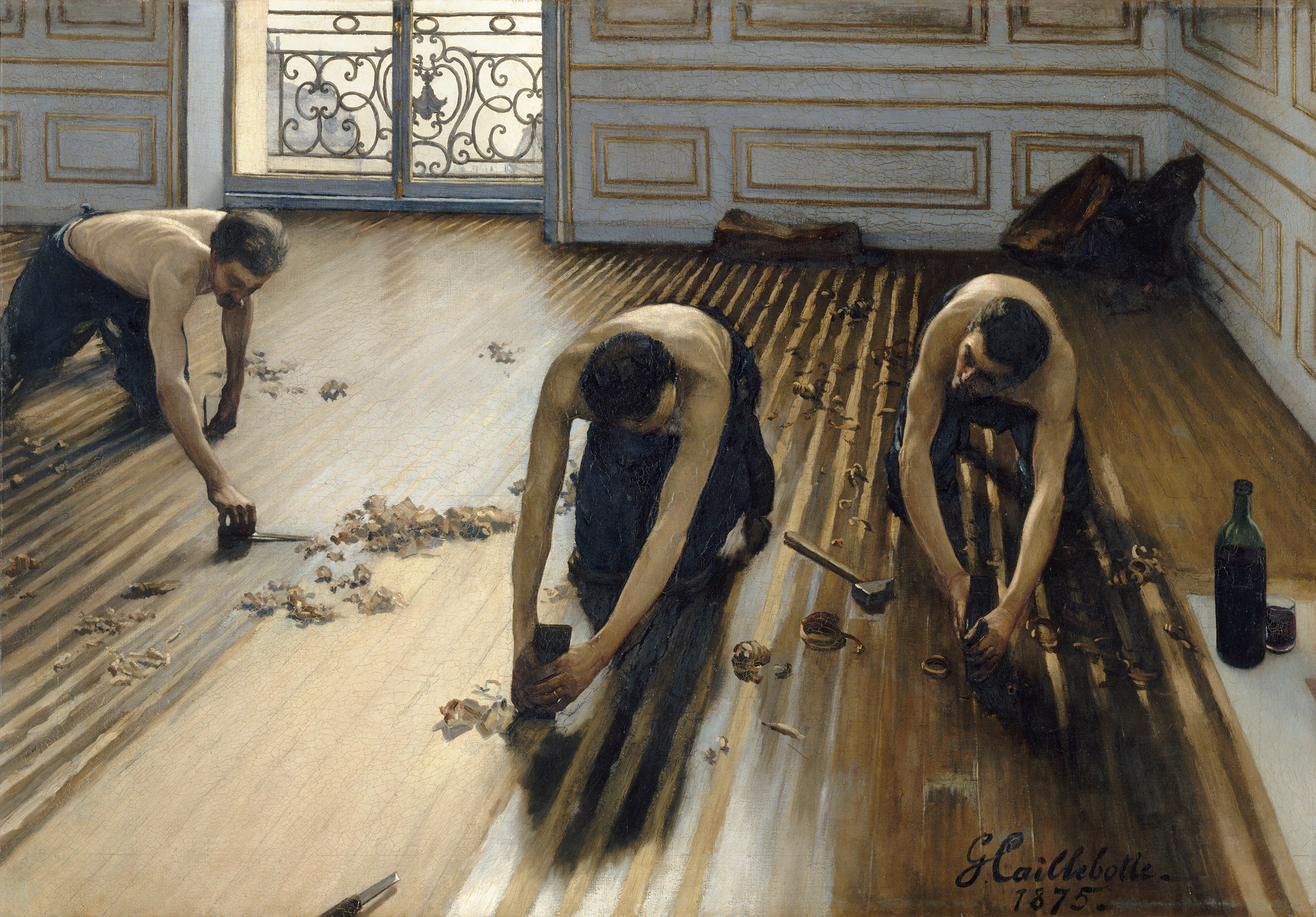

Gustave Caillebotte’s L’Yerres, effet du pluie (fig. 4) shows the rippling effect of raindrops on the surface of the Yerres River from the vantage point of a walking path at the Caillebotte family estate outside Paris. Caillebotte was a young artist from a wealthy family who had trained at the École des Beaux-Arts before joining the Impressionist group. In 1875, he submitted his first major work, The Floor Scrapers (fig. 5), to the Salon and it was rejected. Rather than resubmitting his work, he aligned himself with the Impressionist group and quickly became their principal organizer and investor. This painting, in the museum’s collection since 1971, was made in the summer of 1875. It was the artist’s first summer in Yerres after the death of his father and a sense of absence and loss pervades many of Caillebotte’s works from the period, including this landscape. Like Monet, Caillebotte was an avid boatsman and he included a small skiff on the opposite riverbank.

Gustave Caillebotte (French, 1848–1894). The Floor Scrapers, 1875. Oil on canvas, 40 1⁄8 x 57 5⁄8 in. Musée d’Orsay, Paris, Gift of Caillebotte’s heirs through the intermediary of Auguste Renoir, 1894, RF 2718

In addition to these paintings by Monet and Caillebotte, the Eskenazi Museum of Art has a number of works on paper by Impressionist artists, including Degas, Pissarro, and Renoir. A highlight from the museum’s collection of Impressionist prints is Mary Cassatt’s The Coiffure (fig. 6). Part of a series of color prints that Cassatt made between 1890 and 1891, the print was made through a complex process that involved using drypoint lines to establish the composition, applying aquatint to build tone, and then printing the plates with colored inks. A protégé of Degas, the American-born Cassatt was best known for her paintings, pastels, and prints of women in social and domestic settings. Cassatt participated in four of the eight Impressionist exhibitions and continued to exhibit regularly in Paris after 1886, showing a group of ten color prints with the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel in 1891.4

Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926). The Coiffure, 1890–91. Color aquatine and drypoint on paper, 17 1/8 x 11 15/16 in. Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 76.145

By 1886, the Impressionist exhibitions had expanded to include the next generation of avant-garde artists. Paul Gauguin, Odilon Redon, Georges-Pierre Seurat, and Paul Signac all showed works at the group’s final exhibition in Paris. Although the composition of the group had shifted drastically since 1874, their mission remained the same: to show their works in an independent group exhibition that was not subject to the whims and politics of the state-sponsored systems. Through these pursuits, their innovative compositions and experiments with the effects of light and color helped shape an artistic movement and, in turn, the history of modern art.

Galina Olmsted, PhD

Assistant Curator of European and American Art

Notes

1 They came closest in 1867 and 1868, when the group petitioned for a state-sponsored exhibition of works rejected by the Salon jury. The administration, led by Émilien de Nieuwerkerke, would not agree to a Salon des refusés, and the group was unable to raise the funds necessary to mount their own counter exhibition. These efforts were led by Bazille, who would never see the independent exhibitions realized. Shortly after the outbreak of the Franco Prussian War in July 1870, he enlisted in a Zouave unit of the French Army. He was killed at the battle of Beaune-la-Rolande on November 28, 1870. For a complete history of these events, see Jane Mayo Roos, Early Impressionism and the French State (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

2 “Il y a là évidemment une voie nouvelle ouverte à ceux qui pensent que l’art pour se développer, a besoin d’une somme de liberté plus grande que celle qui lui est octroyée par l’administration,” Emile Cardon, “Avant le Salon,” La Presse (April 28, 1874), 3, as cited in Ruth Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886, Documentation (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), vol. I: Reviews, 12–14.

3 Louis Leroy, “L’Exposition des impressionnistes,” Le Charivari (April 25, 1874), 79–80, as cited in Berson 1996, I: 25–26.

4 Exposition Mary Cassatt (Paris: Galeries Durand-Ruel, 1891).

Share this feature

How to cite this page

Olmsted, Galina. "Impressionism at the Eskenazi Museum of Art." Collections Online. Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 2020. https://artmuseum.indiana.edu/collections-online/features/impressionism-at-eskenazi-museum.php.