On view February 5–May 22, 2022

On view February 5–May 22, 2022

Stuart Davis’s mural Swing Landscape was commissioned in 1936 for the Williamsburg Houses, one of the first federally subsidized housing projects in the United States (figs. 1-2). It was one of seventeen murals commissioned to adorn the communal social rooms of the site’s housing blocks. Ultimately, this ambitious public art project was not fully completed, and only five murals were installed in the housing project when it opened for occupancy in 1938. Both the murals and the housing project itself were products of New Deal programs instituted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to combat the Great Depression during the 1930s. The Williamsburg Houses were constructed under the auspices of the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), while the public art commissioned for this site was designed by artists employed by the Federal Art Project (FAP). Despite the truncated nature of the associated public art commission, the Williamsburg Housing Project was an unprecedented achievement, offering quality affordable housing in a cutting-edge modernist style. Although such an approach to housing was new to Americans, it had become standard in Europe by the 1930s. Indeed, European mass housing geared toward the middle and working classes provided an important model for American reformers and architects seeking to improve and democratize access to quality housing in the United States. To fully appreciate the aesthetic, political, and ideological contexts in which Swing Landscape originated, it is necessary to gain insight into the European housing revolution, whose influence is apparent in the design and concept of the Williamsburg Housing Project.

Figs. 1–2

Top: Stuart Davis (American, 1892–1964), Swing Landscape, 1938, oil on canvas, 86 3/4 × 173 1/8 in. (220.3 × 439.7 cm), Allocated by the U.S. Government, Commissioned through the New Deal Art Projects, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 42.1; Bottom: William Lescaze (1896–1969), architect, Williamsburg Housing Project, Brooklyn, New York, 1938. Photo: Jenny McComas.

“Wohnen Lernen” / Learning to Live: Holistic Approaches to Housing after World War I

Between the world wars, both the United States and Europe faced housing shortages and a lack of quality affordable housing. To address the housing shortage in Europe, a crisis exacerbated by World War I, many local governments and labor unions proactively sponsored ambitious building projects, resulting in the construction of approximately six million new homes between 1919 and 1933. This new housing—primarily in the form of large-scale apartment blocks or modestly sized, densely built private homes—was concentrated in cities and suburban areas and was overwhelmingly geared toward the working classes. Although the building boom spanned the continent, a particular vision—known in Germany as “wohnen lernen” (learning to live), signifying a radically holistic approach to housing—was concentrated in central and northern Europe. City planners and architects strove to take residents’ health and wellbeing into account by considering that housing was connected with all aspects of life, beyond simply providing shelter. Therefore, these modern homes were outfitted with up-to-date appliances and plumbing, and were designed to allow for maximum exposure to sunlight and fresh air. More important, all the new developments included large amounts of landscaped green space, which was considered essential for good health. And most also integrated a variety of social and medical services, including clinics, nursery schools and kindergartens, communal laundries, libraries, and shops.

American housing reformers of the interwar era observed the transformation of European housing with envy and frustration. In her 1934 book Modern Housing, the affordable housing advocate Catherine Bauer defined modern housing as providing “certain minimum amenities for every dwelling: cross ventilation, for one thing; sunlight, quiet, and a pleasant outlook from every window; adequate privacy, space, and sanitary facilities; children’s play space adjacent. And finally it will be available at a price which citizens of average income or less can afford.” But she concluded that “very nearly none” of the existing American housing stock met these criteria.1 After all, housing reforms were initiated in Europe under very different circumstances than those in the United States. Following World War I, socialist governments and strong labor unions emerged in Europe in response to severe economic decline and political unrest, and it was these entities that most successfully facilitated the construction of new, modern housing. In the United States, by contrast, a more conservative political landscape and a strong ideal of individual home ownership prevented direct government sponsorship of planned housing developments.

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

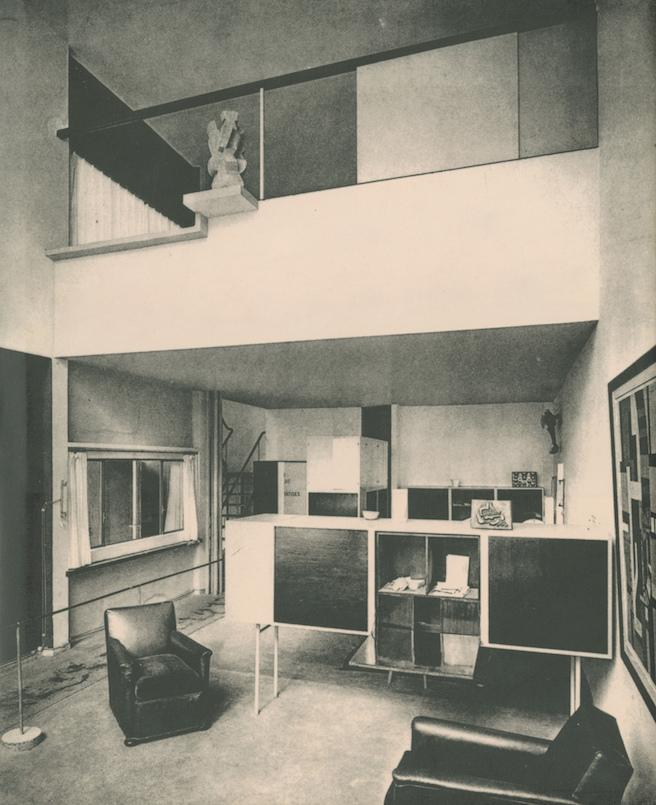

Le Corbusier (1887–1965) and Pierre Jeanneret (1896–1967), architects, Building 13 (interior), Weissenhofsiedlung, Stuttgart, Germany, 1927. Photo: Jenny McComas.

European architects and their clients were also far more open to experimental aesthetic approaches than their American counterparts. Whereas American architecture in the 1920s was dominated by historicist approaches (such as Tudor Revival or neo-colonial), European architects such as Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius pioneered architectural approaches that sought to make houses into “machines for living,” emphasizing efficiency and healthfulness—symbolized as much by the clean lines of the buildings as by their open floorplans and modern furniture and appliances (fig. 3). While eliminating extraneous decoration, most architects nevertheless insisted upon high-quality materials and construction, whether designing private villas for wealthy patrons or urban apartment blocks for working-class residents.

Urban Housing in Postwar Amsterdam and Vienna

The cities of Vienna and Amsterdam were among the earliest pioneers of urban mass housing designated for the working classes. Following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Viennese elected a Social Democratic city council, whose ambitious social and economic programs earned the city the moniker “Red Vienna.” One of its most significant initiatives was the construction of new housing. In Amsterdam, trade unions sponsored the construction of new housing. In both cities, the prevailing architectural styles contained expressionist elements and references to indigenous architectural forms. The Amsterdam complex known as Het Schip, completed in 1921, is representative of architectural work produced by the Amsterdam School, characterized by the use of decorative brickwork, tile, and stone carving. Commissioned by Eigen Haard, a factory workers’ housing association, and designed by Michel de Klerk, Het Schip’s undulating façades give it a sculptural, even playful, quality (figs. 4-5).

Figs. 4–5

Left: Michel de Klerk (1884-1923), architect, Het Schip, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1919-21. Photos: Jenny McComas

Architecturally, the Viennese housing complexes, known as Gemeindebauten, evoke the expressionist ethos of Het Schip. The Rabenhof complex, built between 1925 and 1928 by architects Hermann Aichinger and Heinrich Schmid, for example, features decorative elements that include pointed archways and chevron-patterned brickwork (figs. 6-7). The complex is built over the existing street grid, but archways over the streets provide an enclosed feel, recalling the city’s traditional residential architecture, characterized by apartment buildings opening onto enclosed courtyards accessible from the street via a covered archway (Durchgang).

Figs. 6–7

Heinrich Schmid (1885-1949) and Hermann Aichinger (1885-1962), architects, Rabenhof, Vienna, Austria, 1925-28. Photos: Jenny McComas

A similar, though more monumental, blending of modernist and Viennese indigenous architecture characterizes the Karl-Marx-Hof, a complex that stretched more than 1.2 kilometers (fig. 8). The highest concentration of Viennese mass housing, anchored by the nine-story Reumannhof (fig. 9), was constructed along the Margaretengürtel, a ring road that became known as the “Ringstrasse of the Proletariat”—a reference to the Ringstrasse, the stately nineteenth-century boulevard surrounding the city’s historic core. The prestigious Ringstrasse was home to museums, the opera house, and government buildings. The different architectural emphasis of the two ring roads starkly symbolized the shift that Vienna had undergone during World War I, transitioning from an imperial capital to a provincial city committed to socialist ideals.

Figs. 8–9

Karl Ehn (1884–1987), architect, Karl-Marx-Hof, Vienna, Austria, 1926–30. Photos: Jenny McComas

Berlin Modernism

Although American housing reformers studied the initiatives of “Red Vienna” with interest, the German approach to workers’ housing resonated more in the United States. As in Vienna, the German postwar housing estates usually incorporated a range of amenities, including medical clinics, kindergartens, laundries, and shops, and prioritized green space, light, and air circulation. But their aesthetic orientation was more distinctly modern than that of the housing constructed in Vienna and Amsterdam. Influenced by the design concepts disseminated by the Bauhaus (the experimental art and design school founded in 1919 by architect Walter Gropius), a movement known as the Neues Bauen (New Building) arose in Germany in the 1920s. German modernist architects developed a streamlined aesthetic compatible with efficient and economic approaches to construction. Neues Bauen architects pursued a minimalist architectural style devoid of references to traditional and regional architectural typologies. Known as the “International Style,” it exerted an influence on architects worldwide.

Figs. 10–12

Bruno Taut (1880-1938), architect. Top: Siedlung Schillerpark, Berlin, Germany, 1924-30. Bottom left: Weiße Stadt, Berlin, 1929-31. Bottom right: Wohnstadt Carl Legien, Berlin, 1929-30. Photos: Jenny McComas

Berlin developed into a cosmopolitan metropolis during the 1920s, one that attracted migrants from the countryside as well as immigrants from abroad, including the newly formed Soviet Union. It was therefore necessary to construct a large amount of new housing in the city. Much of it was sponsored by the GEHAG (Gemeinnützige Heimstätten-Aktiengesellschaft), a building society that received most of its capital from socialist trade unions. In 1924, Bruno Taut, an architect whose work blended aspects of Bauhaus modernism with Expressionism, was appointed chief architect for the GEHAG. During the remainder of the decade, he designed six urban housing developments around Berlin. All featured apartment blocks arranged around courtyards, providing residents—even in urban districts—access to green space. Despite the similarity in their planning, each housing estate is aesthetically distinct. Siedlung Schillerpark, located in the working-class Wedding district in northern Berlin, is constructed of red brick, revealing the influence of the Amsterdam School (fig. 10). Weiße Stadt (White City) is named for its stark white façades, bearing a closer resemblance to the minimalist architecture promoted by Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Walter Gropius (fig. 11). But Taut’s architectural style is particularly characterized by his use of color. Even the Weiße Stadt buildings contain colorful accents around doors, windows, and stairwells, softening the harshness of the otherwise unadorned façades. Taut’s love of color is also expressed in Wohnstadt Carl Legien, a housing estate constructed in the workers’ district of Prenzlauer Berg. Here, pastel-colored stucco façades are punctuated with primary colors articulating windows and doors (fig. 12).

Models of Modernist Living in Central Europe

As an alternative to urban apartment living, garden suburbs featuring private (though densely built) homes, known in German as Siedlungen (settlements), offered another model for innovative housing in the interwar period. On the one hand a showcase for the new architecture, these developments also brought custom-designed modernist homes into reach for residents with average incomes. The garden suburb concept originated in England, and was embraced in central Europe during the interwar period, in particular by the Werkbund, an organization founded in Germany in 1907 to promote relationships between artists and industrialists. Between 1927 and 1932, various branches of the Werkbund sponsored the construction of model Siedlungen in six central European cities: Stuttgart, Brno, Breslau (Wrocław), Zurich, Vienna, and Prague. Two of the best-known are the Weissenhofsiedlung in suburban Stuttgart and the Werkbundsiedlung in Vienna. Opening in 1927, the Weissenhofsiedlung featured twenty-one buildings (containing sixty residences) designed by seventeen architects.2 Among the participating architects were the most important representatives of the Neues Bauen, including Le Corbusier and Hans Scharoun (figs. 13-14).

Figs. 13–14

Weissenhofsiedlung, Stuttgart, Germany, 1927. Left: Le Corbusier (1887-1965) and Pierre Jeanneret (1896-1967), architects, Building 13. Right: Hans Scharoun (1893-1972), architect, Building 33. Photos: Jenny McComas

Supervised by Viennese architect Josef Frank, the Werkbundsiedlung in Vienna was completed in 1932. Although it occupies only a small plot of land, the Siedlung contains seventy homes. More than thirty architects from around Europe, including Josef Hoffmann of Austria and André Lurçat of France, participated in this project (figs. 15-16).

Figs. 15–16

Werkbundsiedlung, Vienna, Austria, 1932. Left: Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956), architect, Houses 8-11. Right: André Lurçat (1894-1970), architect, Houses 25-28. Photos: Jenny McComas

Modernist Housing in New York

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

Springsteen & Goldhammer, architects, Amalgamated Dwellings (Grand Street Houses), New York, 1930. Photo: Joel Raskin (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Amalcourtyard.jpg)

Exhibitions such as Modern Architecture (1932) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York played an important role in introducing European modernist architecture to American audiences. However, in the United States, the development of mass housing approximating the European models was rare before the 1929 onset of the Great Depression. A notable exception were the cooperative housing ventures sponsored in the late 1920s by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, a trade union representing Jewish garment workers in New York. One of these cooperatives, the Grand Street Houses, was built in Lower Manhattan by the firm Springsteen & Goldhammer (fig. 17). Surrounding a courtyard, the red brick apartment complex evokes the architecture of interwar Amsterdam and Vienna. And like its European counterparts, medical and recreational facilities were also included at the site. Cooperatives like this were made possible by the passage of the 1926 New York State Housing Act, which granted tax incentives for the construction of limited-dividend housing—that is, housing with rents set at below-market rates. But it was only with the creation of the Public Works Administration, one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, and the New York City Housing Authority, both in 1934, that modern housing for America’s working classes would be constructed on a larger scale.

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

William Lescaze (1896–1969), architect, Williamsburg Housing Project (courtyard), New York, 1938. Photo: Jenny McComas.

The Williamsburg Houses exemplifies the ideal that architects and their patrons strove for in planning these first public housing projects in the mid-1930s (fig. 18). Most were closely modeled on their European predecessors, especially German workers’ housing. Designed by the Swiss-born architect William Lescaze, the Williamsburg Houses were constructed on a twelve-square block plot of land in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, New York. Each of the twenty-four-story apartment blocks were situated at a fifteen-degree angle to the surrounding street grid, a placement influenced by German planning concepts and thought to maximize interior light and air circulation. The buildings themselves featured streamlined, modern façades of light-colored brick, punctuated by glazed blue tiles marking entrances and stairwells. Lescaze was familiar with the work of Bruno Taut, and his use of color is reminiscent of Taut’s; not coincidentally, both architects also occupied themselves with easel painting, which helped them hone their sense of color.

Art and Architecture

Figs. 19–20

Left: Fernand Léger (1881–1955), Composition, 1924, oil on canvas, 51 1/2 x 39 3/4 in. (130.8 x 101 cm), Jane and Roger Wolcott Memorial, Gift of Thomas T. Solley, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 75.41.1; Right: Le Corbusier (1887–1965), Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau, Exposition des Art Décoratifs, Paris, 1925. Photo originally published in Jean Badovici, “Entretiens ur l’architecture vivante,” L’architecture vivante (autumn/winter 1925).

A notable difference between American and European urban mass housing concerns the integration of art and architecture. In Europe, paintings and murals were often incorporated into modernist houses designed for wealthy clients, and art was featured in some of the model homes and interiors designed in the 1920s. For example, Le Corbusier’s Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau, an interior created for the 1925 Exposition des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, included sculptures by Jacques Lipchitz and paintings by Fernand Léger, including Composition, now in the Eskenazi Museum of Art’s collection (figs. 19-20). Composition belongs to a series of works that Léger termed “mural paintings.” Although they are technically easel paintings, he created them with architectural spaces in mind, seeking a seamless harmony between art and architecture, blending the two-dimensional and the three-dimensional. Other European architects, however, preferred to emphasize the aesthetic qualities of the building materials themselves. For example, Mies van der Rohe’s Villa Tugendhat in Brno (Czech Republic) highlights luxury materials such as rosewood, marble, and ebony (fig. 21).

Figs. 21–22

Left: Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969), architect, Villa Tugendhat (interior), Brno, Czech Republic, 1929–30; Michel de Klerk (1884–1923), architect, Het Schip, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1919–21. Photos: Jenny McComas.

The integration of art, however, was less common in the European housing developments intended for working-class residents. A notable exception is found in the Viennese and Dutch housing developments, which often featured carved sculptural embellishment on the buildings’ façades (fig. 22). Commissioning public art—whether sculptural decoration in Europe or murals in the United States—was a means of employing artists and artisans and ultimately strengthening the economy, an important consideration at a time of worldwide economic depression. But perhaps most important, the priority placed on art, aesthetics, and design in interwar housing—especially in the context of housing constructed for working-class residents—represented new modes of thought about the dignity and value of human life, regardless of class, status, or profession.

Further Reading about Modern Housing between the World Wars

- Bauer, Catherine. Modern Housing. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1934.

- Blau, Eve. The Architecture of Red Vienna, 1919–1934. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999.

- Bloom, Nicholas Dagen. Public Housing that Worked: New York in the Twentieth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

- Hardy, Charles O. The Housing Program of the City of Vienna. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1934.

- Miller, Barbara Lane. Architecture and Politics in Germany, 1918–1945. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968.

- Pommer, Richard. “The Architecture of Urban Housing in the United States during the Early 1930s.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 37, no. 4 (December 1978): 235–64.

- Radford, Gail. Modern Housing for America: Policy Struggles in the New Deal Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- Rodgers, Daniel T. Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Stern, Robert A. M., Gregory Gilmartin, and Thomas Mellins. New York 1930: Architecture and Urbanism between the Two World Wars. New York: Rizzoli, 1987.

- Wiedenhoeft, Ronald. Berlin’s Housing Revolution: German Reform in the 1920s. Ann Arbor: UMI Research, 1985.

- To learn more about the Werkbundsiedlung in Vienna, visit the city's informational site.

- To learn more about the Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart, visit the Weissenhof Museum in the Le Corbusier House's website.

- To learn more about the Berlin housing estates designed by Bruno Taut and designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008, visit the UNESCO page about the estates.

- To learn more about the Williamsburg Houses in New York, visit the Living New Deal page about the project.

Jenny McComas

Curator of European and American Art

This feature was produced in conjunction with the exhibition Swing Landscape: Stuart Davis and the Modernist Mural, on view at the IU Eskenazi Museum of Art February 5–May 22, 2022. Research and photography for this feature were generously funded by a grant from the Terra Foundation for American Art.

Notes

1 Catherine Bauer, Modern Housing (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1934), xv.

2 The Weissenhofsiedlung was badly damaged during World War II and about half of the buildings were destroyed.

Share this feature

How to cite this page

McComas, Jenny. "Modernist Housing Between the World Wars: Aesthetics, Politics, and Economics." Collections Online. Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 2022. https://artmuseum.indiana.edu/collections-online/features/european-american/swing-landscape-modernist-housing.php.