Anna Maria van Schurman

Active in: Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark

Alternate names: Anna van Schurman

Biography

Anna Maria van Schurman was born into a wealthy family in Cologne on November 5, 1607. Her parents encouraged various intellectual and artistic pursuits, teaching her to read before she turned four years old. As a child, she studied Latin with her father and brothers, and she excelled at painting, paper-cutting, embroidery, calligraphy and woodcarving. Her classical and artistic education was unusual for a young girl at the time. As a young woman, she was in correspondence with professors of theology and philosophy. Over the course of her life, she would become fluent in fourteen languages, including Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, French, Arabic, and Amharic. Her family moved several times during her youth, settling in Utrecht after the death of her father in 1626.

In the 1630s, van Schurman expanded her artistic ambitions and began to study engraving with Madgalena van de Passe (1600–1638). In 1634, she was invited to write a poem for the opening of the Universiteit Utrecht, then called Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht, and in 1636, she was the first woman to enroll in a course of study there, albeit unofficially. She was required to sit behind a screen or in a curtained booth in the lecture hall so that the other students could not see her. According to her contemporaries, she had an excellent command of mathematics, astronomy, and geography, in addition to her achievements in the classics and in the arts. Her treatises in Latin circulated among well-educated circles in Utrecht and she began to publish her work. She wrote extensively about the education of women, arguing that women should be educated in all disciplines but should not apply their education to professional activity, as this would interfere with domestic life. This was considered a radical position for her time.

Beyond her intellectual achievements, van Schurman continued to pursue artistic projects and was the first Dutch artist known to have completed a portrait in pastel. In 1643, she was awarded honorary admission to the St. Luke Guild of Painters in recognition of her accomplishments. By the early 1660s, van Schurman’s interests began to turn towards theological reform. In 1662, she met the defrocked French Jesuit priest Jean de Labadie (1610–1674). When Labadie settled in Amsterdam in 1669 to establish a non-denominational Christian separatist community, van Schurman sold her house and most of her library to join the group that would become known as the Labadists. In March of that year, she published a pamphlet denouncing the Reformed Church, causing an irreparable rift between van Schurman and many of her intellectual contemporaries.

The Labadists left Amsterdam in 1670, eventually settling in Altona, where their community operated a printing press. Followers of the Labadist movement called Labadie “Papa” and van Schurman “Mama”, although the two never married and are not known to have had a romantic relationship. Labadie died in 1674 and van Schurman followed the Labadists to a new community in the village of Wieuwed in Friesland. The scientific illustrator Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717) joined the Labadists in the 1680s. The community grew to over 400 and practiced detachment from worldly values, attempting to live communally and without private property. Van Schurman continued to engage in this theological work and to write until her death in 1678 at the age of 70.

Selected Works

Anna Maria van Schurman, Self Portrait, 1633. Engraving, trimmed along and within platemark, 16.6 x 15 cm. Rhode Island School of Design.

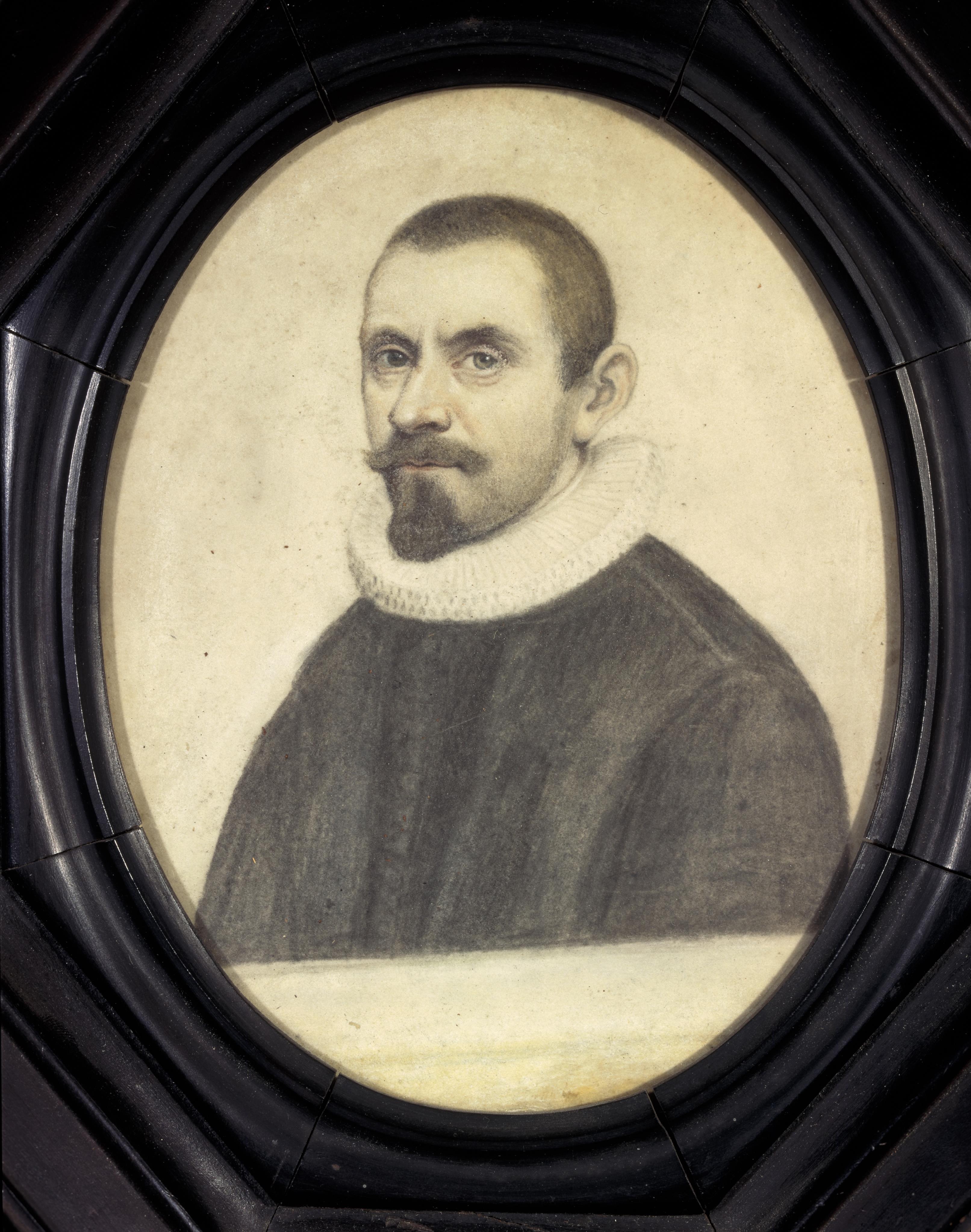

Anna Maria van Schurman, Portrait of Prof. Carolus Dematius, 1597-1651, ca. 1640. Silver pen charcoal on paper, 17 x 10 cm. Centraal Museum, Utrecht.

Anna Maria van Schurman, Portrait of Paul Fleming, Poet and Doctor, 1640. Engraving, 9.8 x 7.7 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

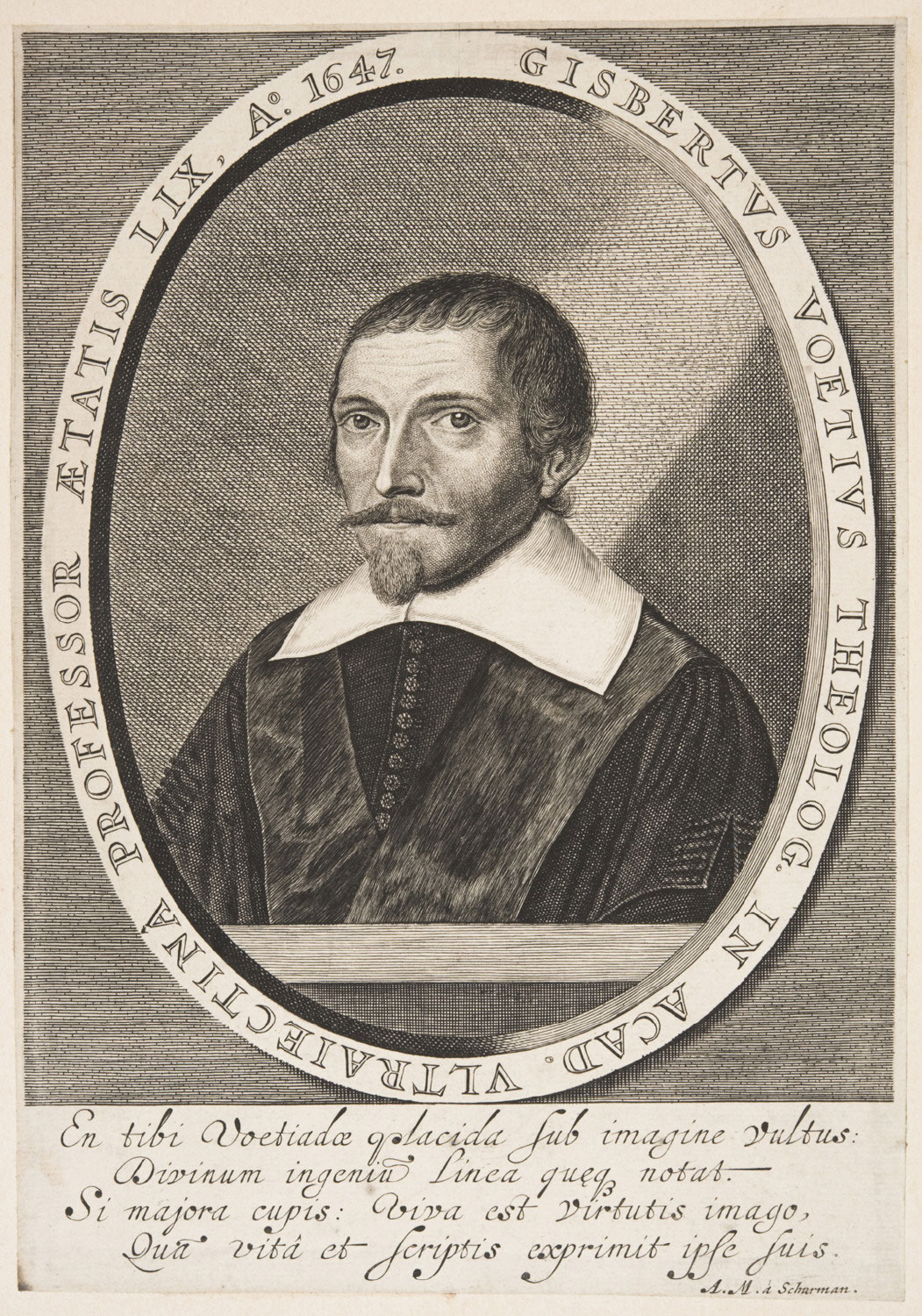

Anna Maria van Schurman, Portrait of Gisbert Voet, the Artist's Teacher, 1647. Etching and engraving, 37.9 x 28 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Circle

Student of

Magdalena van de Passe (1600–1638)

Affiliated with

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717)

Follower of

Jean de Labadie (1610–1674)

Bibliography

Aa, A. J. van der. Biographisch Woordenboek der Nederlanden. Haarlem, 1852–78.

A Checklist of Painters ca. 1200–1976 Represented in the Witt Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London. London: Mansell, 1978.

Bloem, Jeannette. “The Shaping of a ‘Beautiful’ Soul: The Critical Life of Anna Maria van

Schurman.” In Feminism and the Final Foucault, edited by Dianna Taylor and Karen Vintges, 15–27. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004

Borzello, Frances. Seeing Ourselves: Women’s Self-Portraits. New York: Harry Abrams, 1998.

Brouwer, M. “‘Nature’s Masterpiece among Women.’ De wereldlijke roem van Anna Maria van Schurman.” Fryslân 13 (2007): 13–17.

Brouwer, M. “Woman of the World: Anna Maria van Schurman, Celebrity.” The Low Countries. Arts and Society in Flanders and the Netherlands 16 (2008): 302–04.

Bulckaert, Barbara. “Une letter de l’humaniste Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678) sur l’accès des femmes au savoir.” Femmes et Sociétés 13 (2001): 167–83.

Cesena, Domenicus Gilbertus da. La Fama Trionfante, Panegyrico alla Bellissima, Castissima, e Dottissima Signora Anna Maria Schurman. Rome, 1642.

Churchill, Laurie J., Phyllis R. Brown, and Jane E. Jeffrey. Women Writing Latin: Early Modern Women Writing Latin. New York and London: Routledge, 2002.

De Baar, M. “Transgressing Gender Codes. Anna Maria van Schurman and Antoinette Bourignon as Contrasting Examples.” In Women of the Golden Age. An International Debate on Women in seventeenth-century Holland, England, and Italy, edited by E. Kloek, N. Teeuwen, and M. Huisman, 143–52. Hilversum, 1994.

De Baar, Miriam, Machteld Löwensteyn, Marit Monteiro, and A. Agnes Sneller. Choosing the Better Part: Anna Maria van Schurman 1607–1678. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1996.

Demers, Patricia. “Anna Maria van Schurman: The Arts of Argumentation and Self-Portraiture.” In Acta Conventus Neo-Latini Monasteriensis. Brill: Leiden, 2015.

Douma, A. M .H. Anna Maria van Schurman en de studie der vrouw. Amsterdam, 1924.

Duker, A. C. “Briefwisseling tusschen den Utrechtsen kerkeraad en Anna Maria van Schurman.” Archief voor kerkgeschiedenis 2 (1887): 171–78.

Gournay, Marie Le Jars de, Anna Maria van Schurman, and François Poulain de La Barre. The Equality of the Sexes: Three Feminist Tests of the Seventeenth Century. Translated by Clarke Desmond. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Greebe, H. J. G. “Het testament van Anna Maria van Schurman. Met eenige toelichtingen.” Stemmen voor waarheid en vrede. Evangelisch tijdschrift voor de protestantsche kerken 15 (1878): 501–14.

Greer, Germaine. The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and their Work. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1979.

Hautvast, Suzanne. “G. D. J. Schotel over Anna Maria van Schurman. Traditie of een schitterend ongeluk?” Dinamiek. Tijdschrift voor vrouwengeschiedenis 10 (1993): 29–36.

Hollstein, F. W. H. Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts ca. 1450–1700. Amsterdam: Hertzberger, 1949–2010.

Hoogstraten, Monique van. “Mythe in tweevoud. Leven en voortleven van Anna Maria van Schurman.” Master’s thesis, University of Amsterdam, 1993.

Houbraken, Arnold. De groote Schouburgh der Nederlantsche Konstschilders en Schilderessen. 3 vols. The Hague, 1753.

Irwin, Joyce. “Anna Maria van Schurman and Antoinette Bourignon: Contrasting Examples of Seventeenth-Century Pietism.” Church History 60 (1991): 301–15.

Jacob, L. “Elogium erudissimae virginis Annae Mariae a Schurman, Batavae.” In Question celebre. S’il est necessaire, ou non, que les Filles soient sçavantes. Paris, 1646.

Klarenbeek, Hanna. Penseelprinsessen en broodschilderessen: vrouwen in de beeldende kunst 1808–1913. Bussum: Thoth, 2012.

Kloek, Els, Catherine Peters Sengers, and Esther Tobé. Lexicon van Noord-Nederlandse kunstenaressen, circa 1550–1800. Hilversum: Verloren, 1998.

Korte, Anne-Marie. “Verandering en continuïteit. Over de ommekeer van Anna Maris van Schurman en Mary Daly.” Mara. Tijdschrift voor feminisme en theologie 1 (1987): 35–44.

Larsen, Anne R. Anna Maria van Schurman, ‘The Star of Utrecht:’ The Educational Vision and Reception of a Savante. London: Routledge, 2016.

Larsen, Anne R. “A Women’s Republic of Letters: Anna Maria van Schurman, Marie de Gournay and Female Selfpresentation in Relation to the Public Sphere.” Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal 3 (2008): 105–26.

Lee, Bo Karen. Sacrifice and Delight in the Mystical Theologies of Anna Maria van Schurman and Madame Jeanne Guyon. South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press, 2014.

Moffitt Peacock, M. “Paper as Power. Carving a Niche for the Female Artist in the Work of Joanna Koerten.” Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 62 (2012): 238–65.

Moore, Cornelia Niekus. “Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678).” Canadian Journal of Netherlandic Studies 11 (1990): 25–32.

Mülhaupt, Erwin. “Anna Maria van Schürman, eine Rheinländerin zwischen zwei Frauenleitbildern.” Monatshefte für evangelische Kirchengeschichte des Rheinlandes 19 (1970): 149–61.

Münch, Brigit Ulrike, Andreas Tacke, Markwart Herzog, Sylvia Heudecker, Anja Ottilie Ilg, and Hannah Völker. Künstlerinnen: neue Perspektiven auf ein Forschungsfeld der Vormoderne. Petersberg: Imhof, 2017.

Oosterhuis, R. A. B. “De namen van J.A. Comenius en Anna Maria van Schurman in een oud ‘Liber Amicorum.’” Jaarboek Amstelodamum 24 (1927): 151–55.

Pal, Carol. Republic of Women: Rethinking the Republic of Letters in the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Parker, Rozsika. The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. New York: The Women’s Press, 1984.

Pope-Hennessy, Una. Anna Van Schurman, Artist, Scholar, Saint. London: Longmans and Green, 1909.

Puppel, Pauline. “If She Were a Man: The Life and Work of Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678). Zeitschrift fur Historische Forschung 38 (2011): 148–50.

Schotel, G.D.J. Anna Maria van Schurman. Hertogenbosch: Gebroeders Muller, 1853.

Schurman, Anna Maria van. Whether a Christian Woman Should be Educated and Other Writings from her Intellectual Circle. Translated by Joyce L. Irwin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Sneller, A. Agnes. “Een geleerde vrouw: Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678) als literaire person.” Literatuur 6 (1993): 321–28.

Stevenson, Jane. Women Latin Poets: Language, Gender and Authority, from Antiquity to the Eighteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Stighelen, Katlijne van der. “Anna Maria van Schurman ‘die wetenschap had, met eenen diamant op het glas geestig te schrijven.” Antiek 19 (1985): 513–23.

Stighelen, Katlijne van der. “Portretjes in ‘Spaens loot’ van de hand van Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678).” De zeventiende eeuw 2 (1986): 27–44.

Stighelen, Katlijne van der. Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678) of ‘Hoe hooge da teen maeght kan in de konsten stijgen.’ Symbolae Facultatis Litterarum et Philosophiae Lovaniensis. Series B, vol. 4. Louvain, 1987.

Stighelen, Katlijne van der. “Constantijn Huygens en Anna Maria van Schurman: veel werk, weinig weerwerk…” De zeventiende eeuw 3 (1987): 138–48.

Thieme, Ulrich, and Felix Becker. Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler: von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Leipzig: Seemann, 1907–50.

Thomas, Emily, ed. Early Modern Women on Metaphysics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Van Beek, Pieta. Klein werk: de Opuscula Graeca Latine et Gallica, prosaice et metrica van Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678). Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch Universiteit Uitgevers, 1997.

Van Beek, Pieta. “‘One Tongue is Enough for a Woman’ The Correspondence in Greek between Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678) and Bathsua Makin (1600–167?).” Dutch Crossing 19 (1995): 24–48.

Van Beek, Pieta. ‘Over God.’ Een onbekend florilegium van Anna Maria van Schurman (ca. 1625). Ridderkerk: Provily Pers, 2013.

Van Beek, Pieta. De eerste studente: Anna Maria van Schurman (1636). Utrecht: Matrijs, 2004

Van Beek, Pieta. ‘Verbastert Christendom.’ Nederlandse gedichten van Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678). Houten: Den Hertog, 1992.

Van Elk, Martine. Early Modern Women’s Writing: Domesticity, Privacy and the Public Sphere in England and the Dutch Republic. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Van der Stighelen, Katlijne and Mirjam Westen. Elck zijn waerom: vrouwelijke kunstenaars in België en Nederland 1500–1950. Ghent: Ludion, 1999.

Venesoen, Constant. Anne Marie de Schurman: Femme Savante (1607–1678). Paris: Honoré Champion, 2004.

Verhave, J. and J. P. “Konststuckjes van snijden.” De Nederlandsche Leeuw 130 (2013): 164–70.

Verheggen, Evelyne M.F. Beelden voor passie en hartstocht: bid- en devotieprenten in de Noordelijke Nederlanden, 17de en 18de eeuw. Zutphen: Walburg, 2006.

Verwey, S. “Anna Maria van Schurman, in derzelever leven, bekwaamheden en zedelijk karakter (1). Eene voorlezing, gedaan, in het departement Dordrecht, der Maatschappij: Tot Nut van ‘t Algemeen, den 29 maart 1827.” Recensent, ook der Recensenten 20 (1827): 445–66.

Voisine, J. “Un aster éclipsé: Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678).” Etudes Germaniques 27 (1972): 501–31.

Von Wurzbach, Alfred. Niederländisches Künstler-Lexikon auf Grund archivalischer Forschungen bearbeitet. Vienna: Halm and Goldman, 1906–11.

Waller, F. G. and Willem Juynboll. Biographisch woordenboek van Noord Nederlandsche graveurs. Amsterdam: Israël, 1974.