Diana Scultori

Active in:

Alternate names: Diana Mantuana, Diana Ghisi

Biography

One of Europe’s earliest female printmakers, Diana Scultori (also known as Diana Mantuana or, erroneously, as Diana Ghisi) became sixteenth-century Italy’s most famous woman engraver and the first to sign her prints. One of five women artists mentioned in Giorgio Vasari’s 1568 edition of his Le vite de’ piu eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori, Scultori is the only one whom Vasari met. She was born in Mantua in 1547 to Giovanni Battista Mantuano (Scultori) (1503–1575), a sculptor and engraver, and his wife Osanna de Aquanegra. Her brother Adamo Scultori (1530–1585) was also an artist. As the first woman artist to sign her prints, Scultori became one of the first woman printmakers who used that signature to establish various connections to her father, and later to her husband, Francesco Capriani dal Volterra (1535-1594) whom she married in 1575. She was also the first artist known receive a papal privilege to publish her prints, a privilege granted to her in Rome in 1575 by the Bolognese Pope Gregory XIII (1502-1585).

Scultori lived in an era when family names were rare and first names were often added to second names referencing regions or towns of origin, to professions, as well as to relationships, ie. son of, city of. Scultori’s father used similar forms: calling himself Giovanni Battista Mantuano, describing himself as being from Mantua, and Giovanni Battista Scultori, indicating his profession as sculptor. Scultori adopted more forms of signatures than most artists, some of which help us date certain works. On occasion, she used more than one signature on the same plate. Her signatures reflect her connection to her father, her husband, and to cities, including Mantua where she was born; Volterra, her husband’s hometown which granted her honorary citizenship in 1579; and Rome.

Her signatures include: "Diana," "Diana Filia," (Diana the daughter), “Diana F” (Diana made this); "Diana Mantuano," "Diana Mantovana,"(Diana from Mantua--probably used after she moved to Rome in 1575) "Diana Sc. Mantuana," (Diana engraver from Mantua for which Sc. stands for Sculpsit or Scultor.) "Diana Mantuana Civis Volaterana" (Diana of Mantua, Citizen of Volterra) “Diana Mantuana eiusdem Fran(cis)ci uxor Roma incidebat” (Diana of Mantua, wife of Franciscus made this in Rome). She never used the signature Diana Scultori, a name assigned to her by modern scholars, based on the second name “Scultori” used by her father.

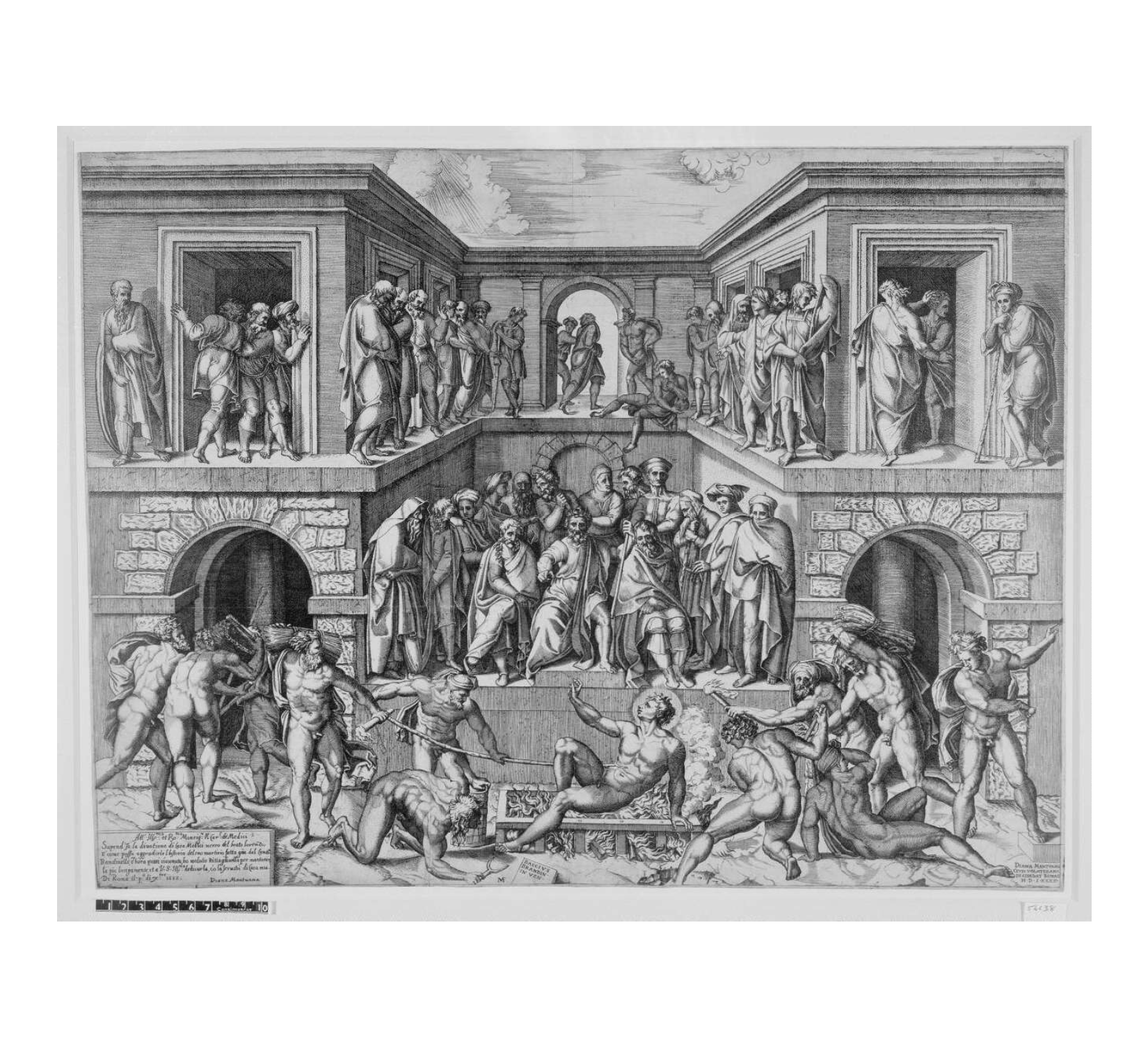

Whether or not Diana served a formal apprenticeship with her father or was given private lessons when time permitted is not known. Undoubtedly, Giovanni Battista taught his daughter the art and practice of engraving. As was typical for the period, her earliest source material was the drawings and paintings by other masters; the artists whose works Scultori quoted include her father, Marcantonio Raimondi (c. 1470/82 – c. 1534), Daniele da Volterra (1509-1556), Federico Zuccaro (1540/41-1609), and Baccio Bandinelli (1520-1560). Just when Scultori began to make prints is unknown, but she was already a proficient engraver when Vasari met her in 1566.

Sometime before June 1575, Scultori married the architect Francesco Capriani Volterrano, who had worked in Mantua some years earlier. On December 29, 1575, her father died. By then Scultori and her husband had been in Rome for six or more months, having settled into a house on the Campo Marzio. After her father’s death, Scultori’s widowed mother joined them. Scultori received her papal privilege on June 5, 1575, which gave her the right to market her prints and protected her against pirated copies for ten years. Having obtained this protection, Scultori first undertaking was to issue a series of ambitious prints, dedicated to members of the extended Gonzaga family.

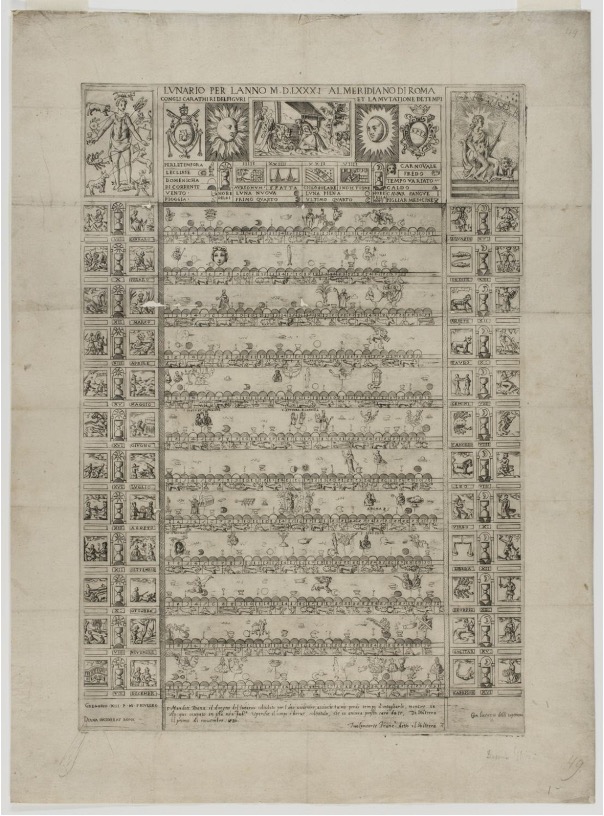

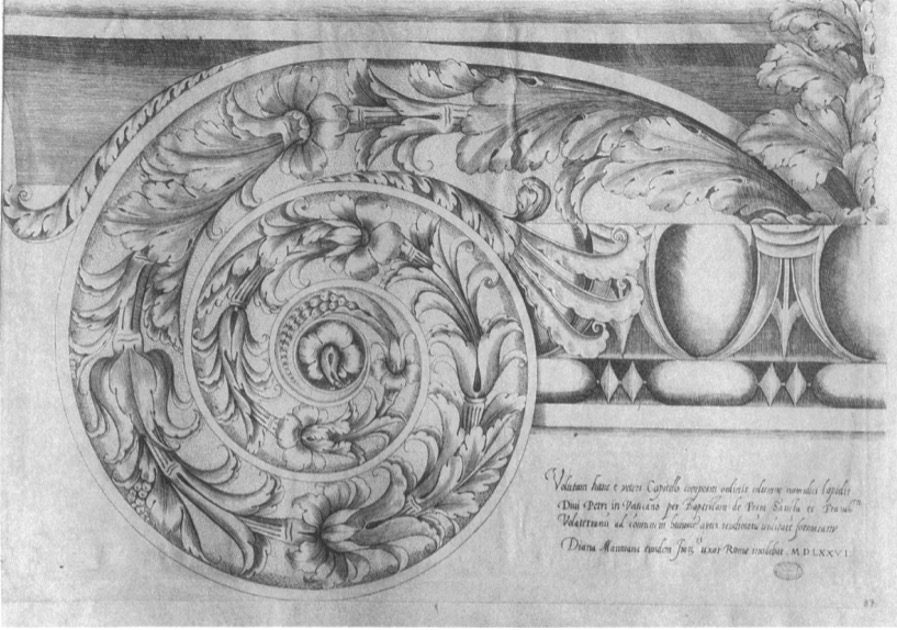

In 1576, Scultori issued prints related to her husband’s drawings of architectural motifs, intended for use by students. The inscription on one such print, now in the collection of the Biblioteca universitaria Alessandrina, reads: “This volute from an ancient capital Numidian stone column, of the composite order, in St Peter’s in the Vatican, was drawn by Francesco da Volterra and Baptista di Pietra Santa for the common use of the students of this art. Diana Mantuana, wife of the same Francesco, engraved it. 1576.” Between 1580 and 1586, Scultori and her husband also collaborated on a Lunario–an astrological almanac printed for general use, and thus presumably sold for income to support their household. Based on astrological motifs found in the Sala dei Venti of the Palazzo del Te in Mantua, Scultori boldly credits her husband “Francesco da Volterra, Architetto” very prominently along the top page, while her own signature at the bottom is secondary in terms of scale and, thus, importance. When Sixtus V (1521 – 27 August 1590) became Pope in 1585, he declared these kinds of astrological calendars heretical, putting an end to this joint venture between husband and wife.

Scultori’s only known child, Giovanni Battista Capriani, was born on September 2, 1578. In 1579, Scultori was granted honorary citizenship in Volterra and in 1580, she was admitted to the Congregazione di S. Giuseppe, an artisan’s confraternity in Cagli. Around this time, a medal was commissioned in her honor. During her active years in Rome, Scultori produced over forty known works. Her last known dated work, The Entombment of Christ, after Paris Nogari (ca. 1536–1601), dated 1588, was previously thought to mourn the death of her husband. He is now known to have died in 1594, which suggests the affliction she so boldly inscribed into the engraving–VIDE DOMINE AFFICTIONE MEA (See, oh God, my affliction)—may refer to the loss of her ability to work due to an ailment, perhaps arthritis. She is not known to have made any engravings after 1588. After she was widowed in 1594, she married another architect, Giulio Pelosi (b. 1567), in 1596. She died on April 5, 1612, in Rome. Many of her copper plates survived and were reprinted in the centuries ahead.

Selected Works

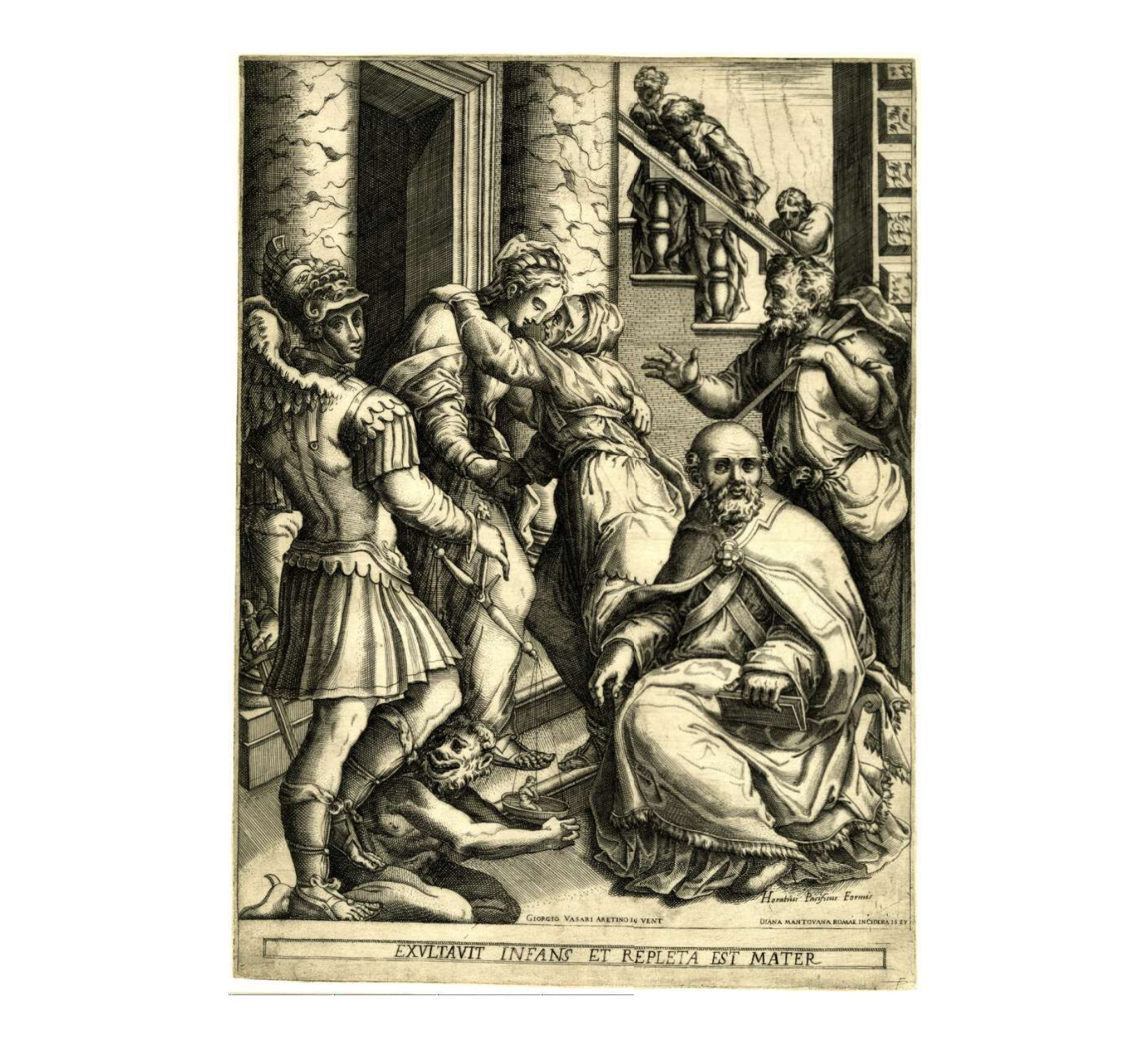

Diana Scultori after Giulio Romano (1499–1546), Birth of Saint John the Baptist, 1555–88. Engraving, 46.8 x 30.2 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Circle

Acquaintance of

Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574)

Daughter of

Giovanni Battista Mantuano (Scultori) (1503–1575)

Sister of

Adamo Scultori (1530–1585)

Wife of

Francesco Capriani dal Volterra (1535-1594)

Wife of

Giulio Pelosi (b. 1567)

Bibliography

Bellini, Paolo, ed. L’opera incisa di Adamo e Diana Scultori. Venice: Neri Pozza Editore, 1991.

Boorsch, Suzanne, and John T. Spike. Italian Artists of the Sixteenth Century. Vol. 31, The Illustrated Bartsch. New York: Abaris Books, 1986.

Boorsch, Suzanne. “Vincenzo Cenzi, Erased Publisher.” Source: Notes in the History of Art 31/32, no. 4/1 (2012): 51–57.

Borea, Evelina. “Le Stampe Dai Primitivi E L'avvento Della Storiografia Artistica Illustrata.” I. Prospettiva 69 (1993): 28–40.

Brodsky, Judith K. “Some Notes on Women Printmakers.” Art Journal 35, no. 4 (1976): 374–77.

Bury, Michael. “The Italian Renaissance Printmaker.” Print Quarterly 18, no. 1 (2001): 90–92.

Bury, Michael. “Infringing Privileges and Copying in Rome, c. 1600.” Print Quarterly 22, no. 2 (2005): 133–38.

Cellauro, Louis. “‘Monvmenta Romae’: An Alternative Title Page for the Duke of Sessa’s Personal Copy of the ‘Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae.’” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 51/52 (2006): 277–95.

Cinci, Annibale. “Francesco Capriano e Diana Mantovana.” In Dall’Archivio di Volterra, memorie e documenti. Volterra: Tipografia Volterrana, 1885

Cohen, Elizabeth S. “Open City: An Introduction to Gender in Early Modern Rome.” I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance 17, no. 1 (2014): 35–54.

Esposito, Donato. “The Print Collection of Sir Joshua Reynolds.” Print Quarterly 28, no. 4 (2011): 376–81.

Facchinetti, Simone. “Salmeggia Profano.” Prospettiva 125 (2007): 53–56.

Fiori, Maria. “The Print Collection of Francesco Ricchino.” Print Quarterly 27, no. 4 (2010): 359–71.

Frazier, Alison. Review of Writing on Hands: Memory and Knowledge in Early Modern Europe, by Claire Richter Sherman.” Libraries & Culture 38, no. 1 (2003): 75–76.

Girondi, Giulio. “Diana Mantovana’s Virgin and Child with St John the Baptist.” Print Quarterly 29, no. 3 (2012): 297–99.

Gregory, Sharon. Review of The Invention of the Italian Renaisssance Printmaker by Evelyn Lincoln. Renaissance Quarterly 57, no. 3 (2004): 1001-002.

Grelle Iusco, Anna, ed. Indice delle stampe intagliate in rame a bulino e in acqua forte esistenti nella stamperia di Lorenzo Filippo de’Rossi. Rome, 1996.

Grieco, Sara F. Matthews. Review of Donna, disciplina, creanza cristiana dal XV al XVII secolo, Studi e testi a stampo, by Gabriella Zarri. Archivio Storico Italiano 155, no. 2/3 (572/573) (1997): 541–46.

Griffiths, Antony, Anne Röver-Kann, Ralph Hyde, Richard Kendall, Peter Black, and Giorgio Marini. “Notes.” Print Quarterly 12, no. 3 (1995): 289–97.

Hill, George Francis. “Timotheus Refatus of Mantua and the Medallist ‘T. R.’” The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Numismatic Society 2 (1902): 55–61.

King, Catherine. “Looking a Sight: Sixteenth-Century Portraits of Woman Artists.” Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte 58, no. 3 (1995): 381–406.

King, Catherine. “An Etching and Lelio Orsi’s House.” Print Quarterly 23, no. 2 (2006): 176–82.

Lafranconi, Matteo. “Antonio Tronsarelli: A Roman Collector of the Late Sixteenth Century.” The Burlington Magazine 140, no. 1145 (1998): 537–50.

Lincoln, Evelyn. “Making a Good Impression: Diana Mantuana's Printmaking Career.” Renaissance Quarterly 50, no. 4 (1997): 1101–47.

Lincoln, Evelyn. The Invention of the Italian Renaissance Printmaker. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000.

Lincoln, Evelyn: The Invention of the Italian Renaissance Printmaker. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000.

Lincoln, Evelyn. “Invention, Origin, and Dedication: Republishing Women’s Prints in Early Modern Italy.” In Making and Unmaking Intellectual Property: Creative Production in Legal and Cultural Perspective, edited by Mario Biagioli, Peter Jaszi, and Martha Woodmansee, 339–58. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Lord, Carla. “Raphael, Marcantonio Raimondi and Virgil.” Notes in the History of Art 3, no. 4 (1984): 81–92.

Marcucci, Laura. Francesco da Volterra: Un protagonista dell’architettura post-tridentina. Rome: Multigrafica, 1991.

Massari, Stefania. Incisori mantovani del ’500: Giovan Battista, Adamo, Diana Scultori e Giorgio Ghisi dalle collezioni del Gabinetto Nazionale delle Stampe e della Calcografia Nazionale. Rome: De Luca, 1980.

McDonald, Mark P. “Printmakers in the Age of Humanism.” Print Quarterly 20, no. 4 (2003): 412–15.

Necipoglu, Gülru. Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power: The Topkapi Palace in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1992.

Pagani, Valeria. “A Lunario for the Years 1584–1586 by Francesco da Volterra and Diana Mantuana.” Print Quarterly 8 (1991): 140–45.

Pagani, Valeria. “Adamo Scultori and Diana Mantovana.” Print Quarterly 9, no. 1 (1992): 72–87.

Parshall, Peter. “Antonio Lafreri’s Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae.” Print Quarterly 23 (2006): 3–28.

Pouncey, Philip. “The ‘Spinario.’” The Burlington Magazine 102, no. 685 (1960): 167–69.

Princeton University Art Museum. “Acquisitions of the Art Museum 1985.” Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University 45, no. 1 (1986): 16–42.

Rebecchini, Guido. “Sculture E Scultori Nella Mantova Di Giulio Romano. 2. Giovan Battista Scultori E Il Monumento Di Girolamo Andreasi (con Una Precisazione per Prospero Clemente).” Prospettiva, no. 110/111 (2003): 130–39.

Santoro, Enza Fioroni. “Le Stampe Nelle Biblioteche Italiane: Principi Di Una Rinnovata Catalogazione E Progetti per Un Catalogo Unico a Carattere Internazionale.” La Bibliofilía 57, no. 1 (1955): 47–55.

Sherman, Claire Richter ed. Writing on Hands: Memory and Knowledge in Early Modern Europe. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001.

Spencer, John R. Andrea del Castagno and His Patrons. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991.

Standen, Edith A. “The Sujets De La Fable Gobelins Tapestries.” The Art Bulletin 46, no. 2 (1964): 143–57.

Stefani, Chiara. “Giacomo Franco.” Print Quarterly 10, no. 3 (1993): 269–73.

Tanzi, Marco. “Ipotesi per Un Perduto ‘San Girolamo’ Di Giulio Campi.” Prospettiva 67 (1992): 79–82.

Vasari, Giorgio. Le vite de’ piu eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori. Florence, 1568. ed. G. Milanesi. Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, edited by G. Milanesi. 10 vols. London: Macmillan-Medici Society, 1912–15.

Wallace, Richard W. “Salvator Rosa’s ‘Death of Atilius Regulus.’” Burlington Magazine 109/772 (July 1967): 393–97.

Witcombe, Christopher L. C. E. Copyright in the Renaissance: Prints and the Privilegio in Sixteenth-Century Venice and Rome. Brill: Leiden and Boston, 2004.

Wood, Jeremy. “Cannibalized Prints and Early Art History: Vasari, Bellori and Fréart De Chambray on Raphael.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 51 (1988): 210–20.

Zarri, Gabrielle. Donna, disciplina, creanza cristiana dal XV al XVII secolo, Studi e testi a stampo. Rome: Edizioni di storia e letteratura, 1996.