Artemisia Gentileschi

Active in: Italy and England

Alternate names: Artemisia Lomi Gentileschi

Biography

Born in Rome on July 8, 1593, Artemisia Gentileschi became one of the most significant artists of the seventeenth century. She was the eldest child of Prudenzia di Ottaviano Montoni and the painter Orazio Gentileschi (1563–1639), who was her first teacher. Her mother died when she was just thirteen years old, and she began to paint in her father’s studio before she was fifteen. Her earliest works demonstrate the clear influence of her father’s Caravaggisti style but even as a young artist, she distinguished herself through her naturalistic approach. Her earliest surviving work, Susanna and the Elders (1610), was completed when she was just seventeen years old.

The following year, Gentileschi experienced a personal tragedy that would shape her public reception in the years ahead. She was raped by the painter Agostino Tassi (1580–1644), who was working with her father to complete a commissioned project inside the Palazzo Pallavicini-Respigliosi. After the rape, Gentileschi began a relationship with Tassi with the expectation that he would marry her to restore her virtue. In 1612, when it became clear that he would not marry her, Gentileschi’s father pressed charges against Tassi for violating the Gentileschi family’s honor. During the subsequent trial, Gentileschi was tortured to ensure that her testimony was accurate. Tassi was exiled from Rome, but the verdict was later annulled and the sentence was not enforced. This course of events shaped how Gentileschi’s work was received by feminist art historians in the twentieth century.

A month after the trial, Gentileschi married the Florentine painter Pierantonio Stiattesi (b. 1584) and moved to Florence, where she would live for six years. This was a transformative period for her art, as she became a successful court painter who enjoyed the patronage of the Medici family. She was the first woman accepted into the Accademia della Arti del Disegno and completed several significant works, including Judith Slaying Holofernes (1612–13) and Judith and her Maidservant (1613–14). While in Florence, Gentileschi and her husband had five children, of which only one, a daughter called Prudenzia (b. 1618), lived into adulthood. It is known that she was a painter who trained with her mother, but no works have been securely attributed to her. Gentileschi and her family faced personal, legal, and financial trouble that necessitated their return to Rome in 1620.

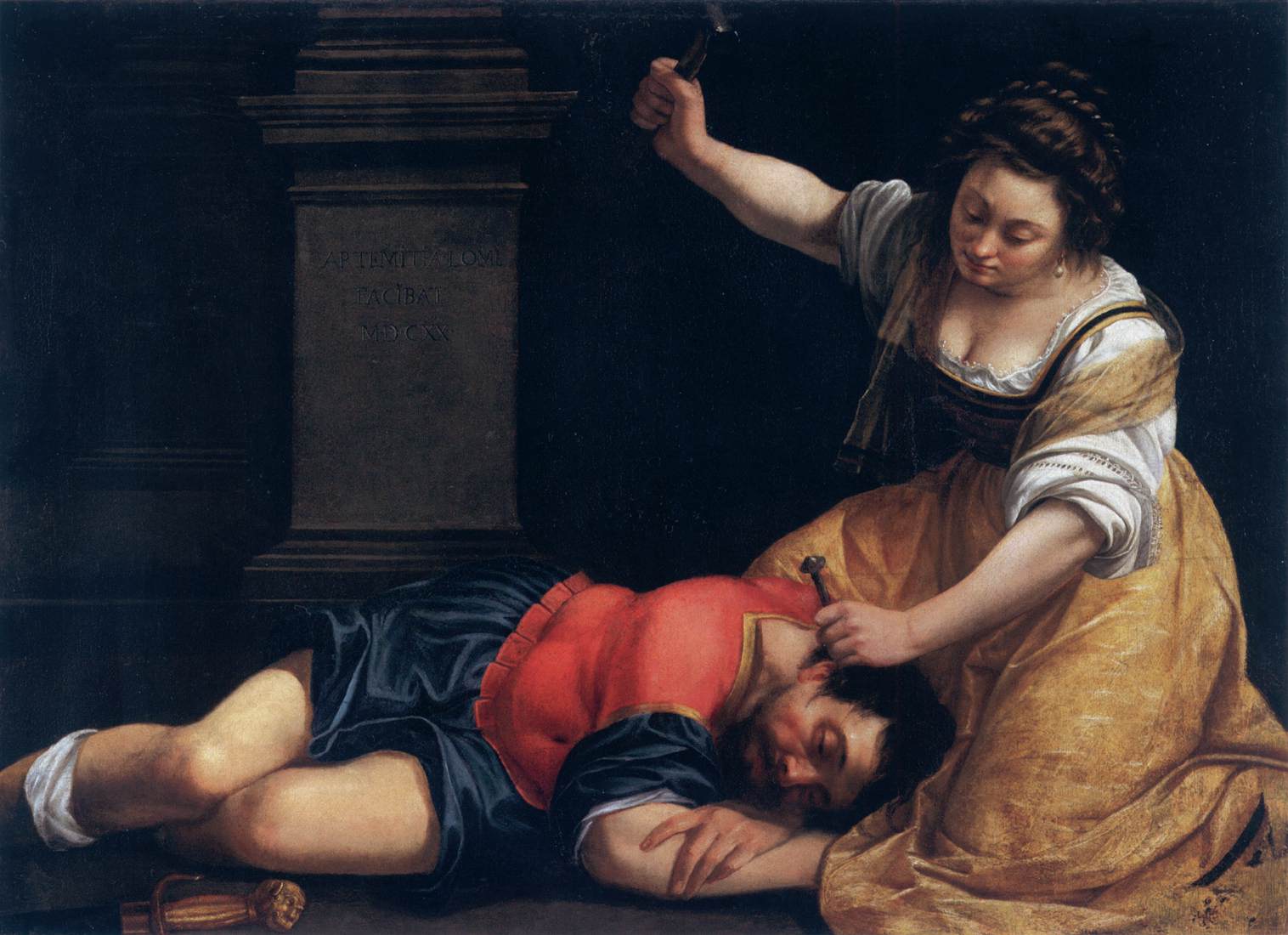

Gentileschi found success in Rome and was able to secure the patronage of a number of art collectors throughout the city. During this period, she made significant works such as her Jael and Sisera (ca. 1620), and the version of Judith and her Maidservant (ca. 1623–24) that is now at the Detroit Institute of Art. There are no extant records of her husband after 1623 and limited documentation makes it difficult to fully recover her travels in the decades ahead, but Gentileschi lived in Venice from 1626 or 1627 until she moved on to Naples in 1630. She did some travel outside of Naples, including a trip to London to join her father at the court of Charles I (1600–1649) in 1636, but otherwise she seems to have remained in Naples for the rest of her life. A painting made during this period, David with the Head of Goliath, has recently been attributed to her when a 2020 restoration revealed a previously obscured signature.

Her father died suddenly in 1639. The remaining years of Gentileschi’s life are fairly opaque as compared to the early Roman and Florentine periods. She continued to paint, mostly by commission. Historians traditionally dated her death to 1652/53 but some evidence has indicated that she was completing commissions as late as 1654, working closely with a studio assistant called Onofrio Palumbo (1606–1656). Many art historians believe that she died in 1656, during the Naples Plague, which killed roughly half of the Neapolitan population.

Selected Works

Artemisia Gentileschi, Susanna and the Elders, 1610. Oil on canvas, 170 x 119 cm. Schloss Weißenstein, Pommersfelden.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and her Maidservant with Head of Holofernes, ca. 1623–25. Oil on canvas, 184 x 141 cm. Detroit Institute of Arts.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist, ca. 1610–1615. Oil on canvas, 84 x 92 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and her Maidservant, 1613–14. Oil on canvas, 114 x 93.5 cm. Palazzo Pitti, Florence.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes, ca. 1614–1620. Oil on canvas, 199 x 162 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, ca. 1618–19. Oil on canvas, 77 x 62 cm. National Gallery, London.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Jael and Sisera, 1620. Oil on canvas, 86 x 125 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest.

Circle

Mother and teacher of

Prudenzia [Gentileschi] Stiattesi (b. 1618)

Daughter and student of

Orazio Gentileschi (1563–1639)

Wife of

Pierantonio Stiattesi (b. 1584)

Friend of

Simon Vouet (1590–1649)

Friend of

Virginia Vezzi (1600–1638)

Friend of

Giovanna Garzoni (1600–1670)

Friend of

Michelangelo Buonarotti the Younger (1568–1646)

Friend of

Pierre Dumonstier II (1568–1646)

Employer and teacher of

Onofrio Palumbo (1606–1656)

Bibliography

Barker, Sheila. "The first Biography of Artemisia Gentileschi: Self-fashioning and Proto-feminist Art History in Cristofano Bronzini’s Notes on Women Artists." Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes 60 (2018).

Barker, Sheila. "A new document concerning Artemisia Gentileschi's marriage." The Burlington Magazine 156, no. 1341 (2014): 803-804.

Berger, Robert W. "Artemisia's Self-Portraits." The Art Bulletin 62, no. 1 (1980): 97-112.

Bissell, R. Ward. Artemisia Gentileschi and the Authority of Art Critical Reading and Catalogue Raisonné. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999.

Bissell, R. Ward. "Artemisia Gentileschi: Painter of Still Lifes?" Source: Notes in the History of Art 32, no. 2 (2013): 27-34.

Bissell, R. Ward. "Artemisia Gentileschi's Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting." The Art Bulletin 68, no. 3 (1986): 421-437.

Bruno, Simone, Ferruccio Petrucci, and Anna Impallaria. "Judith and Holofernes: Reconstructing the History of a Painting Attributed to Artemisia Gentileschi." Heritage 2, no. 3 (2019): 2183-2192.

Christiansen, Keith. "Becoming Artemisia: Afterthoughts on the Gentileschi Exhibition." Metropolitan Museum Journal 39 (2004): 101-126.

Christiansen, Keith, and Judith W. Mann. Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art and New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001.

Cohen, Elizabeth. "The Trials of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Rape as History." The Sixteenth Century Journal 31, no. 1 (2000): 47-75.

Dabbs, Julia K. "Sex, Lies, and Anecdotes: Gender Relations in the Life Stories of Italian Women Artists, 550-1800." Aurora: The Journal of the History of Art 6 (2005): 17-39.

Garrard, Mary D. Artemisia Gentileschi and Feminism in Early Modern Europe. London: Reaktion Books, 2020.

Garrard, Mary D. Artemisia Gentileschi around 1622: The Shaping and Reshaping of an Artistic Identity. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001.

Garrard, Mary D. Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Garrard, Mary D. "Artemisia Gentileschi's Self Portrait as the Allegory of Painting." The Art Bulletin 62, no. 1 (1980): 97-112.

Harris, Ann Sutherland. "Artemisia Gentileschi and Elisabetta Sirani: Rivals or Strangers?" Woman's Art Journal 31 (2010): 3-12.

Locker, Jesse M. Artemisia Gentileschi: The Language of Painting. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015.

Lutz, Dagmar. Artemisia Gentileschi: Leben und Werk. Stuttgart: Belser, 2011.

Mann, Judith W. Artemisia Gentileschi: Taking Stock. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2006.

Papi, Gianni, Simon Gillespie, and Tracey D. Chaplin. "A David and Goliath by Artemisia Gentileschi rediscovered." The Burlington Magazine, 2020.

Solinas, Francesco, Michele Nicolaci, and Yuri Primarosa. Artemisia Gentileschi, the Story of a Passion. Rome: De Luca Editori d’Arte, 2011.

Spinosa, Nicola, and Francesca Baldassari. Artemisia Gentileschi e il suo tempo. Milan, Italy: Skira, 2017.

Straussman-Pflanzer, Eva. Violence and Virtue: Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith Slaying Holofernes. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2013.

Treves, Letizia. Artemisia. London: National Gallery, 2020.

Zarucchi, Jeanne Morgan. "The Gentileschi 'Danaë': A Narrative of Rape." Woman's Art Journal 19, no. 2 (1998-1999).

Entry Notes

Dedicated to Diane DeGrazia, brilliant scholar, good friend, and wonderful board member.—Heidi Gealt